The Turing Test

First we shape our tools, and then our tools shape themselves through us. And then maybe they shape themselves without our help... With the explosion in generative AI that happened at the end of 2022, the future of AI is unclear but exciting or terrifying (or both). I will say a few words about platforms like ChatGPT at the end of this lesson, but it begins with a more historical look at how Artificial Intelligence has been thought about in human culture, and often still is. I'll look briefly at some basic ways people thought about AI in the 20th century, and a bit about how things seem to have been actually coming together in the 21st. Many of the "20th century" ideas still shape most people's views on AI today, though that is changing as we see how AI is actually developing (just another of the many tools in our toolbox?). After looking at the traditional ideas about AI as a machine that "thinks like a human" (or better than a human), we will move on to examine some ways in which our own human intelligence may interact with, rely on, or be influenced by the use of computers and eventually (increasingly) by artificial intelligence itself. In other words (gotcha), it is not really so much about the exciting breakthroughs in AI being made today (a bit more about those in the last lesson, though). It is, however, about how ordinary humans tend to think about AI, and perhaps how they should be thinking about and using it.

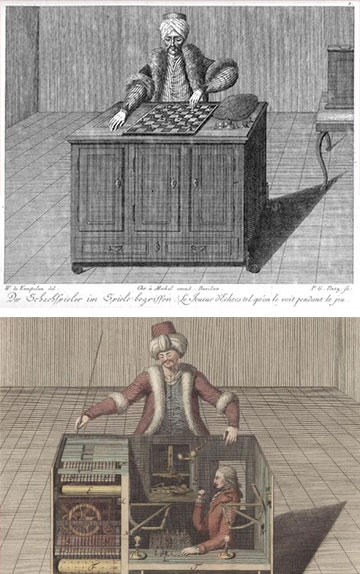

“The Turk” – a chess playing "automaton" created by Wolfgang von Kempelen, 1770 . Actually, a hidden human player was controlling the moves.

While the possibility of "thinking machines" is centuries old, the phrase "artificial intelligence" only appeared in the 1950s with the creation of the earliest computers. Those first computers were able to do equations accurately and quickly, store and sort data, and perform logical processes reliably and swiftly. The early designers and users of these giant, lumbering machines sometimes saw the speed and accuracy of computation as the first steps toward the automation of human thought, an Industrial Revolution of the mind.

Most of what we will be looking at in the second half of this course involves the effect of the computer - and its offshoots in networking, the Internet, and digital technologies generally - on human society and culture. The upshot of the computer revolution is something most of you live within every day. Even if you have no idea how your devices work, or struggle to use them sometimes, I'm sure it is obvious to you that computer technology has profoundly affected how humans behave, interact, think of themselves - and think.

Do we actually want machines that can think "like humans"? Is such a machine possible? Do we have it now? Will we have it soon? Would such machines be our slaves (ugly thought, more on that later), masters (scary thought, though they might be better masters than other humans tend to be), or friends (comforting thought, but can machines really feel, care, empathize? Can we really be their friends? Can we trust them? Would we actually be better off with a ChatGPT-like companion than a real human friend? It seems like that is where some people are headed. Can we trust AI to be loyal friend, or will it be the most manipulative psychopath imaginable?).

Machines that think like humans?

To return to the birth of the computer in the 1940s and 50s, the most famous figure in this revolution was an Englishman named Alan Turing, and he seems to have thought that true Artificial Intelligence would indeed "think like a human being" - or at least seem to.

Turing had been a code breaker for the allies during World War II, and was instrumental in creating the theoretical groundwork for the cryptographic intelligence that would help beat the Germans. After the war, Turing turned his brain towards the future of computing and the question of artificial intelligence. In a landmark 1950 article entitled "Computer Machinery and Intelligence," Turing laid out his plan for a test to establish whether or not a computer could convince a human being that it was a human.

The Turing Test

A person sits at a keyboard, typing questions. Those questions are sent to the next room, in which either another human or a computer program responds. If the first person believes they have had a conversation with the human when in fact they have been conversing with the computer program, then that program has passed the Turing test. It has convinced a human being that it is also a human being.

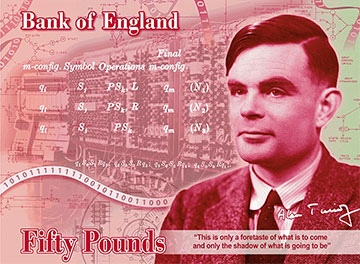

Persecuted during his own life because of his homosexuality (which was illegal in England at that time!) Alan Turing is now the face on Britain's polymer £50 note

In his 1950 article, Turing acknowledged, then dismissed, objections to his central question: "Can machines think?" He considered the possibility that only humans could have a soul, the idea that a thinking machine was too scary to contemplate, and the possibility that there were mathematical or physical limitations to the computing power of machines that would make it impossible for them ever to achieve even the appearance of human conversationalists. In the end, however, he argued that it was only a matter of time before artificial intelligence would reach the level of human intelligence. He suggested that a very human activity could be used as a benchmark for testing the progress that was being made:

We may hope that machines will eventually compete with men in all purely intellectual fields. But which are the best ones to start with? Even this is a difficult decision. Many people think that a very abstract activity, like the playing of chess, would be best. (Turing, 1950)

If beating a human at chess really is a valid test of human-like intelligence, as Turing supposed, then the defeat of human chess master Garry Kasparov by the IBM supercomputer "Big Blue" in 1997 might have satisfied Turing that a computer had reached the level of human intelligence, even though no program has actually so far passed the original Turing Test to everyone's satisfaction. Many now feel that the test is not actually a very well thought-out one anyway, and recommend a different set of parameters to determine if an AI can fool a human. (See, for example, Teich 2019.)

It is still debatable whether any AI has so far passed the Turing test. In early 2023 I asked ChatGPT whether it could pass the Turing test, and it generated this answer (in part): "While I can generate human-like responses and simulate a conversation, I may not be able to consistently exhibit the full range of cognitive abilities required to pass the Turing Test."