Better killing through technology

World War II (1939-1945) brought many new advances in the mechanization of killing: Messerschmidts and Spitfires, submarines, jet fighters and long-range guided V2 rockets. The war was brought to a close by the dropping of the new atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Two bombs killed over 350,000 people and levelled large parts of the cities they were exploded over. Lingering radiation and radiation poisoning killed many survivors and made the areas uninhabitable. Harry S. Truman, the U.S. President who had given the go-ahead for the bombings, had toured the burned-out remains of Berlin a month earlier (the Germans had already surrendered), and in his diary echoed the sentiments of Einstein and others: "I fear that machines are ahead of morals by some centuries and when morals catch up perhaps there'll be no reason for any of it." The machines had made it possible for a human being, such as President Truman, to remotely bring about hundreds of thousands of deaths. Was this not a huge boost to evil? Truman seemed to think so.

Pablo Picasso's modernist masterpiece Guernica, depicting the aerial bombing massacre of civilians in a Basque town during the Spanish Civil War (shortly before World War II; Nazi and Italian planes were "practicing"). This image has become a symbol for the absurd chaotic destruction and mechanized mass killing that came of age in the Second World War.

Yet when I think of the evolution of mechanized killing in the 20th century, it is not first and foremost these weapons of mass destruction that come to mind. It is that supremely inhuman killing machine created by the Nazis for the extermination of Jews and other human beings in their death camps.

If Edwin Black's 2001 book on IBM and the Holocaust is the first real effort to link up our own digital culture to the Nazi's systematized killing, it was well-understood at least by the early 1960s that there were disturbing connections between the capitalist legacy of the Industrial Revolution - mechanization, scientific management, and the Division of Labour - and the inhumanity of the methods the Nazis had adopted. This may have been what the philosopher and sociologist Herbert Marcuse meant when he suggested that

Auschwitz [the most famous of the Nazi concentration camps] continues to haunt, not the memory but the accomplishments of man [emphasis added] - the space flights; the rockets and missiles; the "labyrinthine basement under the Snack Bar"; the pretty electronic plants, clean, hygienic and with flower beds; the poison gas which is not really harmful to people; the secrecy in which we all participate. [...] If the horror of such realizations does not penetrate into consciousness, if it is readily taken for granted, it is because these achievements are (a) perfectly rational in terms of the existing order, (b) tokens of human ingenuity and power beyond the traditional limits of imagination. (Marcuse 1964, 252)

In other words, we focus on how clever we are, and we rarely think at all about the basic assumptions behind industrialization (efficiency, mechanization), even when it comes to killing. The achievements of the 20th century are "haunted" for Marcuse (and many others) by the awareness of how it has been used for inhumane purposes, above all the experiments of the Nazis and the holocaust. What has driven a lot of technological progress, from the jet engine to computers? The desire for power and the will to kill the other.

The Banality of Evil

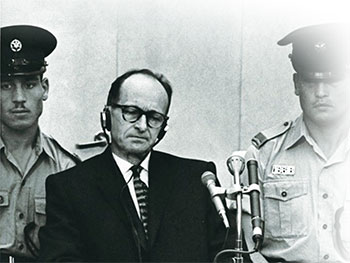

Eichmann on trial in Jerusalem.

When the Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann was brought to trial for his part in arranging the transportion of the Jews to the death camps, the philosopher Hannah Arendt reported on the proceedings in the New Yorker magazine for February 1963 and subsequent issues. In a highly controversial argument, Arendt suggested that Eichmann was not a monster or even so much "evil" in the traditional sense of being devoted to hurting other people. Instead, what Arendt said was evil about Eichmann was that he was just another uninspired bureaucrat, who - in the now classic line - was "only following orders." She famously referred to this version of human monstrousness as "the banality of evil."

Banality means "ordinariness," "everydayness," even "triteness" (something so familiar as to be unworthy of notice). Again and again during the trial, Eichmann showed his de-humanized conception of the process of transporting the Jews as primarily a logistics problem and a bureaucratic challenge. The transportation was a workflow, like the factory assembly line; he himself was an emotionless functionary trying to obey the principles of "scientific management," largely alienated from the monstrous purpose of the process he was managing, much like the guy who organizes the trucks that deliver the chicken parts to McDonalds might have little concern about where the cargo started out from or where it would ultimately end up. The world created by our technology has encouraged a new kind of evil. The evil of a human being becoming a cog in an unthinking and immoral process.

Psychologist Stanley Milgram with his "shock machine".

Arendt's arguments made terrifying sense to the psychologist Stanley Milgram when he was trying to come to grips with the results of his famous shock experiment. The experiment seemed to prove that two out of three otherwise ordinary Americans would deliver potentially lethal doses of electricity to a stranger merely in an effort to perform their part in a psychology experiment and please the authority-figure "scientist" in charge. Reflecting on the results of his experiment, Milgram agreed that the problem with someone like Eichmann was at least in part that he had been raised in a culture that believed in efficient means regardless of the ends, and in which any personal responsibility tended to get obscured within the impersonal structures of bureaucracies and mechanized systems. Milgram concluded that perhaps the chief cause of the horror of modern human "civilization," the horror of Auschwitz and Hiroshima, was the depersonalization and mystification of responsibility caused by ... our old friend the Division of Labour.

The moral world of human beings itself, in a certain sense, has been changed or made problematic by the impersonal structures of mechanized, corporate, bureaucratic society. We are trying to live on a scale that is too much larger than the human animal one we evolved for. It is hard to act morally beyond the narrow interpersonal scale. The hugeness of our institutions, now becoming global, is on a scale in which we find it difficult to think and act as moral beings. Milgram concludes:

There was a time, perhaps, when people were able to give a fully human response to any situation because they were fully absorbed in it as human beings. But as soon as there was a division of labor things changed. Beyond a certain point, the breaking up of society into people carrying out narrow and very special jobs takes away from the human quality of work and life. A person does not get to see the whole situation but only a small part of it, and is thus unable to act without some kind of overall direction. He yields to authority but in doing so is alienated from his own actions.

Even Eichmann was sickened when he toured the concentration camps, but he had only to sit at a desk and shuffle papers. At the same time the man in the camp who actually dropped Cyclon-b into the gas chambers was able to justify his behavior on the ground that he was only following orders from above. Thus there is a fragmentation of the total human act; no one is confronted with the consequences of his decision to carry out the evil act. The person who assumes responsibility has evaporated. Perhaps this is the most common characteristic of socially organized evil in modern society. (Milgram 1973, 77)

It's important to recognize that Arendt and Milgram weren't letting Eichmann off the hook. They did think he was an evil man. Their point was the "banality" of his evil. He wasn't some larger-than-life embodiment of malice, a supervillain. Rather, what was evil about him was his conformism: his obedience to authority, his lack of imagination, his readiness to toe the line, his lack of any personal sense of responsibility for the evil he was taking part in. He was evil, in other words, in the way that many or all of us can be in the system humans currently live within. Just keeping our heads down and doing what the system tells us.