Cold War

For the second part of this lesson, I will be looking at the specific example of the United States, the most heavily armed nation in the world. As with so many (but not all) matters of social change, Canada often tags along in a curious way with the developments in society and culture in that country, and we may collude with and further enable actions of the American government, including military actions. In the second half of the last century, the United States became the undisputed leader of the "free world," largely due to its part in winning World War II, and a flourishing economy while much of the rest of the developed world lay in ruins.

After World War II ended, there was an almost immediate start to an undeclared "Cold War" between the forces that faced each other after having destroyed Germany: the so-called "communist" (really already totalitarian) Soviet Union on the one side, with lands it had taken from the Germans in Eastern Europe, and the democratic republics of England, France, and the United States on the other, with the United States the clear leader as the owners of the atomic bomb and now becoming the new overseas "policemen" of a Europe in shambles.

As discussed by Columba Peoples (2008) in one of the recommended readings for this week, political scientist Stanley Hoffman has identified the underlying "skill thinking" characteristic of postwar American foreign policy. The focus was not on what America was doing in the world, but on how it was doing it - through innovation, ingenuity, technology, independent American know-how.

But this American "skill thinking" had an uncanny similarity to the kind of instrumental, process-oriented thinking that Arendt and Milgram attributed to the Nazis. It was focused on the technical process, less on the morality. It was focused on remaining the strongest power, not on being the most humane or moral actor. "Skill thinking" was an extension of a belief many Americans held that "know-how" and technical expertise were what had made America a world leader, and that the future of America's new dominance on the world stage would be best preserved by technological means. The atom bomb had won the Second World War, and the nuclear arms race would decide the winner of the Cold War. Technical superiority was what mattered most. The assumption that America was always right was a given. The only question was would it be able to maintain its dominance. Technology would be the key. The technology of power and "defense."

Omar N. Bradley, one of the U.S. generals who had won the Second World War, referred to "the permanent American desire to substitute machines for men and magic weapons for conventional armaments" (quoted in Peoples, 58). There was an almost unquestioned idea that with its Thomas Edisons and Henry Fords America had technology and mechanization to thank for its current place in the world. These were the source of American power as well as American economic prosperity, and the two - military power and economic prosperity - would come to be more and more dependent on one another as the Cold War progressed in the 1950s and 60s. The typical American citizen thus felt that technology was the source of their security as well as their prosperity. The fear of "communism" was strong, spread by the government, the military, the CIA, and the popular media. Under the circumstances, proud but fearful Americans rarely questioned military decisions made by the government in the 1950s, and came to accept technologies of death such as nuclear warheads as the price of freedom.

Another American general from the war, Dwight D. Eisenhower, was elected President of the United States and served two terms. He was the president during most of the 1950s. In his Farewell Address as 34th President of the United States in 1961 he coined the term "military-industrial complex," which has become the classic way to refer to how the American military and big business mutually supported one another in the second half of the 20th century.

Eisenhower was both a Republican and a former military leader, but he still wanted to warn the American citizens of the danger to American freedom and livelihood of this collusion between military power and corporate power:

This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence — economic, political, even spiritual — is felt in every city, every statehouse, every office of the federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society. In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists, and will persist. (Eisenhower 1961)

Eisenhower was trying to warn America of the dangers inherent in the military's reliance on manufactured technology, and the complementary reliance of private industry on the military as a "customer." The arms race fueled this collusion, about which Eisenhower turned out to have been right to be anxious. Over the course of the 50s and 60s military spending skyrocketed and the American economy at the same time began to depend upon it to a significant degree. This was the culmination of a process of embroiling the military with the economy that had started at least by the end of the 1800s, but never before had war and arms been so clearly a winning formula for the power-brokers both of military force and of capitalism. Americans love technology; technology is good for business; technology made America great; technology keeps America safe. These were the unquestioned assumptions of many Americans throughout the Cold War era (1947–1991), and indeed they continue to be popular up to present moment. Meanwhile, poor people starved, social programs were stunted and cut at the expense of the military, and corporations that could produce more life-giving products focused on the production of weapons and munitions. What Eisenhower was worried about happened. Public policy was unduly influenced by the powerful combo of the military and big business.

Fear of technology

At the same time as Americans might accept that their safety and well-being were founded on technology, there was also a profoundly felt fear of technology in postwar America. The mechanized murder of Auschwitz, the unprecedented devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the very clear dehumanizing aspect of mechanization in the non-military sphere as well led to an unprecedented "Luddite" reaction that can be most clearly seen in the torrential outpouring of dystopian science fiction during this period - everywhere technology was pictured as alien, out of control, dehumanizing, destructive of human dignity and life.

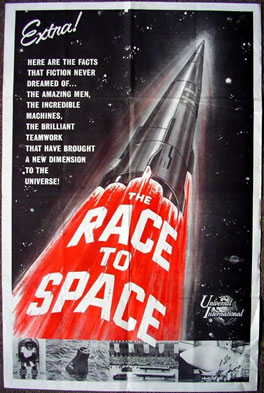

These were fears experienced by human beings throughout the developed world, but Columba Peoples focuses on one specific American terror in the 1950s, a challenge to the whole U.S. "skill-thinking" attitude about itself as world leader [the attitude that all political problems could be solved by exceptional American know-how]): the superiority of Russia's space program.

Because in the 1950s the Soviet Union suddenly leapt ahead of the United States, successfully launching Sputnik, the first artificial satellite to orbit the earth. Later, the Soviets would also pull off the first manned flight in outer space by Yuri Gagarin in 1961. All at once there seemed to be the distinct possibility that Russian ingenuity would outstrip the Americans and lead to a Soviet supremacy in a kind of space-based military power.

American culture from the end of the 50s is suffused with references to Sputnik, most notably in an endless spate of nervous jokes that show how worried Americans actually were. In the anxious depths of the Cold War arms race, Americans were ready to feed the budgets of both the military and the space program if it could help keep them one step ahead of the enemy. Peoples suggests that Eisenhower himself and his inner circle knew that America was not in any serious way technologically behind the Russians, but that the apprehensiveness of the average American citizen well served the growing machine of the "military-industrial complex." The "Space Race" was a simple metric that the ordinary citizen could understand and worry about. It seemed like world domination would extend to the domination of space as well.

Americans were thus both afraid of technology and afraid not to have more of it. So a fundamental belief in technical know-how as the answer to political issues, foreign policy, and any problems of a military kind contributed to a collusion between the military and big business which, as we shall see, only grew to be more accepted after the end of the Cold War around 1990. After World War II Americans came to think of themselves differently: as the policemen of the world, as at risk and in need of constant military-technical advancement, as at risk both from too much technology and not having enough. Competition is at the heart of both capitalism and the military. The fear of losing a contest with the enemy - Russian communism in the 1950s and 1960s, Islamic terrorism and fundamentalism later, once the "communist bloc" collapsed around 1990 (and Chinese technology and economic influence today) - encouraged Americans to double down on the military industrial complex.