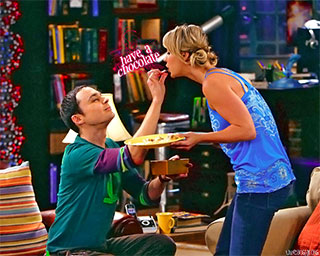

Did you see what Sheldon did last night?

In a sense, then, the hyperreality of modern human life is nothing new. As soon as we started considering symbols and signs to be as meaningful as real things (or actually more meaningful) we were living in a world of what Baudrillard liked to call "simulations."

But there might be reason to worry that the proliferation of mediated and virtual realities available in electronic mass media, and now with digital technology, is dragging us further into the abandonment of lived, physical, non-imaginary, non-simulated reality. We are becoming painfully aware that we do not live in reality, but in this "hyperreality," endlessly transfixed by simulations of reality (images, videos, fictions). Or at least some of us find this possibility poignant. Or at best bitterly funny.

I like to use the example of my own mother here. She spent the last ten years of her life living by herself in her house in the Seattle area, far away from me, her only close relation, and she would spend most evenings with reruns of the television show Big Bang Theory back to back on syndicated tv. The characters on the show were her best friends, or in any case they were the "people" with whom she spent the largest amount of time near the end of her life.

There is nothing that unusual about treating fictional TV characters as though they were real. Whenever someone says "Did you see what Sheldon did last night?!" they are immersed in the "fictional reality" of our hyperreal modern world. Human culture is inherently hyperreal - a mix of lived and mediated reality.

But does the greater replacement of social life by The Spectacle and the greater choice of virtual realities (video games, for instance) mean our lives are getting "more hyperreal" all the time perhaps? And is that okay? A good thing even? Or is it regrettable, something to fight?

Hanging out with some Friends

My mother watched Big Bang Theory because she wanted the illusion of some company in the house with her, and she liked the company of those characters. Sociologists call this kind of activity parasocial interaction, and unless they are in a judgmental or worried mood they don't necessary think of it as a negative thing. It can be "therapeutic" for many people, as long as they don't become obsessed or put themselves in a position to be exploited (by an influencer, say). Human beings can apparently get some of the same benefits they get from real live social interaction through the parasocial experience of watching Friends, for instance. The hyperreal aspect of this, however, is that they are being "social" with non-real (fictional) recordings of people and that the "interaction" is not really interaction. It is one-way. Though you have been affected by these fictional characters from the 1990s, the fictional characters can in no way be influenced or changed by you: they are recorded images, they were fictional to begin with, they can't hear you or see you. Can we really call such interactions "social," or even "interactions"?

Isn't this another of our hyperreal spectator activities? We can get real information about human interaction or understand the world better from watching sitcoms, of course. Or can we? The characters are realistic. Or are they? Do we know? Do we care?

Isn't this another of our hyperreal spectator activities? We can get real information about human interaction or understand the world better from watching sitcoms, of course. Or can we? The characters are realistic. Or are they? Do we know? Do we care?

It seems that we don't, most of us. It's not so much that we don't know that Sheldon or Ross, Rachel, and so forth are fictional characters and not real people, as that we don't seem to care about this distinction as much as we might. We are used to spending a large amount of our time with non-real media projections, images on screens that look something like reality. And they become a big part of our reality. Even if we "know they aren't real." (Do we though? Really?)

What's more, now with the Internet we know "real people" (not fictional characters (?)) that we also experience frequently through the media (our friends on Instagram, for example, and people we have never met in real life whom we have friended or followed, and influencers). The idea of hyperreality suggests that our experience of so much of our "reality" in these mediated ways makes us less clear on the difference between (lived, embodied) reality and (spectated, framed/fictionalized/fictional) media. And as the simulation comes to look and feel more like reality itself (only "better"), or the simulation's "reality" comes to replace physical embodied reality for us more and more of the time, we seem to be less concerned about whether the things we love, the "people" with whom we get emotionally involved, or the situations on which we spend our time and thought and feeling and energy are "real" in the old physical sense or not.

Is that okay? For us? For the rest of the world on whom we disengaged fantasists may still have an impact?

With social media, more and more parasocial relationships can develop with "real" people (as opposed to fictional characters) we've never met, though these "real people" may have been doing their best to simulate the copies of real people simulated on fictional television and/or non-fictional people who have a highly fictionalized representation there, such as celebrities. Do we remember (or care) how unreal all this really is? Maybe sometimes.

The parasocial relationships one has with Internet micro-celebrities or "influencers" can sometimes move into more genuinely interpersonal social relationships, when you contact them and they actually respond to your comments, send you an email, or mention you in a blog or a podcast or YouTube channel or TikTok.

But maybe this only adds to the hyperrealism of the media we are interacting with. There is always a screen between us, a representation of an absent reality - editing, framing, simulation.

And then there is the whole virtual reality scene. A question that interests me: is the hyperreality of human existence in some sense increasing or especially worrying with the kind of virtual realities we can create and experience today (and that we are likely to be able to create in the future)? What happens when there is an interactive, virtual reality simulation of the Friends characters for us to spend the day with? We don't just see and hear them, but we can touch them and smell them and interact with these simulated beings? Will we still care about non-simulated flesh and blood people? And will we all be running around in real life trying to appear as simulated as possible? Are we already doing that? Do we really want to be media? Does it seem like a way to avoid death, and vulnerability, and intimacy, and ... reality - and yet to exist in a more transcendent way, on a screen, in a VR environment, in technology?