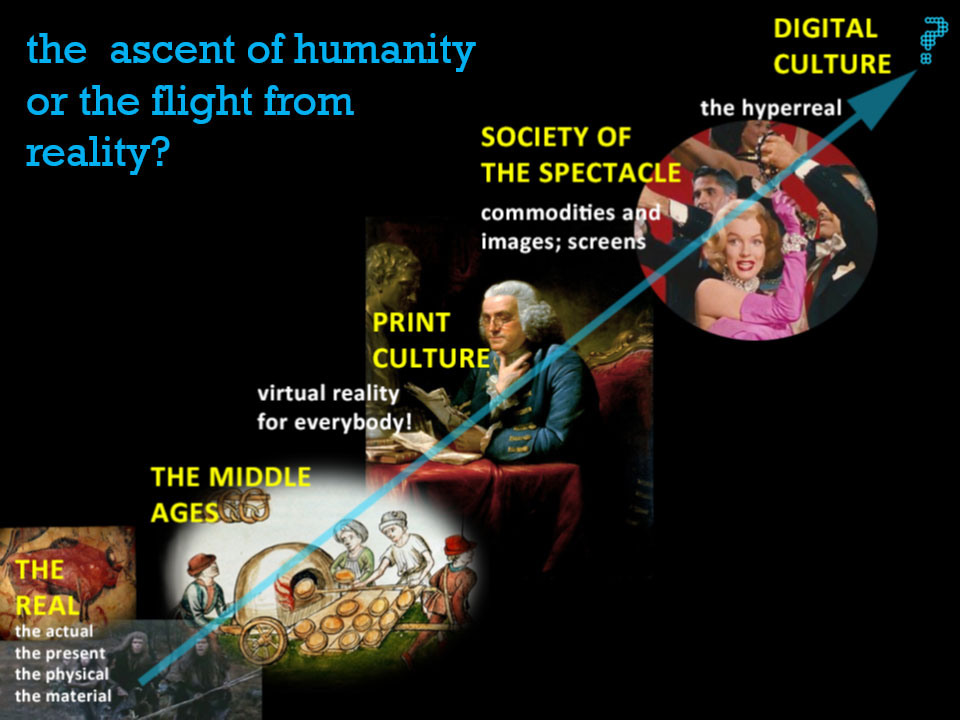

Hyperreality and virtual reality

As I've mentioned, people did sometimes even get lost in the virtual realities of print culture. They came to know the characters and authors of some book more deeply than their parents, children, best friends, and lovers. They might begin to take the world simulated in the book for the real world and they might well slave, sacrifice, or even die for ideas and entities that had no real-world existence. There were even books that dramatized the problems "living too much in books" could lead to, such as Don Quixote or Madame Bovary - those are classic fictional virtual reality critiques of people who put too much of their attention into print culture virtual reality. Pretty meta for back in the day.

Arguably our higher-tech, video virtual realities are a lot more seductive and confusing than the ones in books. And with more technology they will presumably become even easier to mistake for embodied reality - or they may completely replace it, assuming we can somehow stay alive while detaching entirely from our physical existence as animals. RIght now virtual reality is not bad at simulating visual and audible realities. In a 3D movie or immersive video game we can receive many of the same stimuli and cues we get from embodied reality. When the computers can simulate the sensory input of the other three senses as well, we will decidely have more than a testing toe in The Matrix.

Does this really matter? Is it something to worry about, resist? We'll come back to these questions. What difference does it make in the end if I carry on a love affair with a real flesh and blood person or with a computer simulation as long as there is warmth, companionship, empathy, and the sex is good? A question asked and partly answered in the 2014 film Her, where a guy falls in love with his new artificially intelligent operating system. A decade later, some people are now reportedly doing this with their generative AI companions. In the future (assuming we make it there, and somehow all have the wealth and leisure we will need to enjoy the luxuries of technology!), will we each live in our own simulated worlds, which are just as good as - or better than - the real one? Might this be a multimedia all-senses return to the isolationism of print culture virtual life or couch potato tv watching? Is it just human nature to be "escapist"? Does real reality just suck?

It's interesting to me, though, that it seems to be those with the least difficult lives, with the fewest "real" problems (food, shelter, etc) who are most inclined to be escapist. We are privileged to have the leisure to escape (!), even though our reality is pretty cushy by global standards. Perhaps humans did not naturally evolve to be creatures that have so much leisure time and so little need to engage with natural reality.

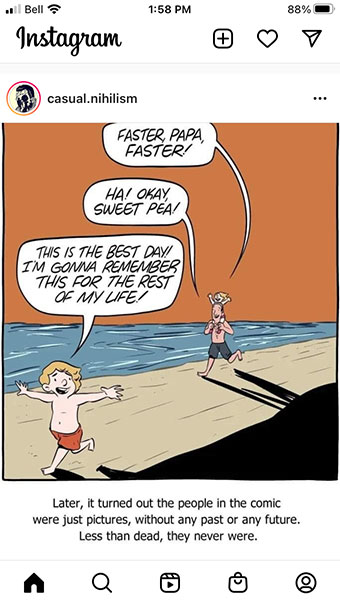

Hyperreality is about the irony that most of us both "know" that the "it" we are with is somehow not real, and yet we still care about it deeply, and even at some deep level usually care if it's real or not. If you really don't care whether something is real or not, then the concept of hyperreality will be meaningless to you.

Vicarious reality

Something is vicarious if you experience it through someone else rather than directly. You watch a rom-com and vicariously experience infatuation, love, or heartbreak, through the characters in the movie. The Spectacle is often there to provide vicarious reality, and we visit it for that. We watch other people's lives, fictional or fictionalized - some of us as much or more than we live our own. We can identify and empathize and have vicarious (simulated, weaker, unreal) experiences through the media.

When I meet my friend Lewis, he immediately starts telling me about some show he is watching, discussing the plot and characters as though they are real people he knows. This never interests me much, because I don't watch many shows and I don't consider what a bunch of fictional people are doing as that illuminating or intriguing - especially since they are mostly criminals with unreal-seeming and not even particularly appealing (to me) lives. But it is very common - at least in my generation - to talk about what the people on the shows one is watching are doing. Virtual gossip, I guess, because their lives are more interesting. They are Mexican drug dealers or Washington power brokers, or whatever. We're just schmos ourselves, leading comparatively undramatic lives.

Sometimes when discussing the impact of technology on us in this class, a student will start talking about what happens in a science fiction movie as evidence to support their view - as though the fictional drama in the movie is part of their personal experience or part of a non-fictional report on human reality. Often, they seem not to take into account that the action they are talking about was made up by somebody, never really happened, whatever truths there might be in it. It's just more media, it's not an experience of of something that really happened. Though I guess it happened to them, while they watched the movie,

Does it matter if it's real?

It seems to me like knowing what is real (lived by real people) and what isn't could be important, for the good of humanity and perhaps even the survival of our species. If you really don't secretly believe that some things are real and some are made-up or fake, the concept of hyperreality can have little meaning for you. It still has meaning for me, though.

The Spectacle by nature flattens out the clear distinction between real and fictional. Media images and television shows tend to package both real and fictional things in much the same way (this was true even before the advent of "reality tv"), and this may add to the increased tension or trouble in the hyperreality of our existence in the modern world as well. Media all comes to us as hard bright unfeeling images, potentially entertainment, whether on tv or through our phones, whether Friends or footage of real carnage from a war or a genocide.

When people attempt to bring their reality into the media - these crucial moves toward inclusivity, environmental realism, and so forth, for example - they are up against the distressing fact that all representations of reality are inherently "fake" in a certain sense - they are not reality; they are images, representations. It is harder and harder to define clearly what makes something real and what makes something fake when we know most of it through representational media, when consuming media makes up such a huge amount of our daily "reality," and the media are getting better all the time at simulating real-seeming things (we'll get to Deep Fakes before the end of the course!).

Those who want to discredit the reality of serious claims for social justice, the legitimacy of the environmental crisis, and so forth, will use the representational falsity of all culture as arguments that all positions are equally falsified representations, your lies as opposed to mine: there is no right or wrong, no truth; all reality is relative, all representation is inherently false. Your news is Fake News. Maybe mine is too. All news is Fake News and I like my Fake News better. Unfortunately, there is probably an element of truth in this irresponsible and uncaring attitude.

Philosophically, it may be true to say that all representation is a falsification of reality; but are some representations not falser than others? Or perhaps more brutally false, more dangerously false? That's the problem that still bothers those of us who care. Stephen Colbert, a hyperreal figure about whom I have very mixed feelings, made a crack at a White House reception in 2006: "Reality has a liberal bias." One of the outfits I follow on Instagram or Facebook has taken this ironic and equivocal pronouncement and made it their genuinely-felt motto. I too tend to think that moving left in politics, moving away from my own blind privilege, and moving closer to our shared humanity is a move toward reality. People who don't agree with me would say that is media bias or my bias, and I can't prove them wrong with logic or images, not entirely. They might need to live it somehow, if I'm right.

The gloomier picture is that the technology and pervasive mediation most of us are absorbed in is divorcing each of us further from reality all the time, giving us more and more unreal experiences that we are happy to take for our reality, buffering us from authentic human interaction with real other people, making real things look more and more like unreal images, and turning our real lives in embodied reality into simulations of the phony Spectacle images we consume all day, dishing up compelling virtual realities until all realities seem virtual, masking reality from us more all the time. Are the media inevitably something between us and reality, between us and real life? A screen? One of Neil Postman's points could be summarized: Television makes real things seem unreal and unreal things seem real. Is that even truer of the Internet? We'll come back to this question in Lesson 6, and throughout the rest of the course really.

What are the consequences for real people when they are treated as hyperreal, like the people we've never met who died in a plane crash we hear reported about on the news, and the loving ones they leave behind? We'll explore one particularly harrowing aspect of this in the next lesson, on war.