"Welcome to the desert of the real"

Much of the second half of this course asks you to think about the question: to what extent can the Internet make us "with it" in a way that television could not, and is that as good as, or better than, unmediated experience?

We know that the Internet can bring us more information than we can actually deal with. The information can come from all sorts of people: those who want to change the world, those who want to shout, those who want to exploit us, those who want to show off, those who want to show their love and generosity, etc etc etc. Those who have a lot of traditional power, and those who don't have all that much (Bill Gates and I both have an account on Twitter/X, or at least we did).

Does that not mean that we are closer to a true picture of reality when we use the Internet? Again, it probably depends on how you define reality. (Also how you use the Internet!) If "reality" means embodied lived experience in the physical and social world, then obviously not (?). If "reality" means the mediated broadcasting of the views of an ever greater number of human beings, then maybe so, and the question becomes more complicated.

While making unprecedented volumes of information available to us if we want it, the Internet also brings a myriad of new "spectacles" to our pockets. Images, images, images ... and not necessarily of reality, needless to say. Our devices bring more of everything, including what's really happening outside of the media, presumably (if we can even still conceive of a world happening apart from the media that represents it - that's part of what hyperreality means, recognizing that reality is always mediated). The media also allow us to detach from reality just as books and television did. Indeed, our pocket devices provide a built-in electronic buffer between ourselves and the physical and social world when we are out in it, a firewall behind which we can hide. In the sidebar reading by Burns and Sawyer (2010), the authors belabour the degree to which people now use technology to "defend" against embodied presence and engagement that they don't want to have. Following Raymond Williams, they describe the new potential to "be" anywhere in the world while remaining safely cocooned at home (or behind your earbuds on the bus) as ‘‘mobile privatization.''

As most of us are aware, our phones may simultaneously put us "in touch" with "people" on the other side of the world whom we have never actually met, while also insulating us from the real people in our lives, across the table from us, or sitting next to us on that bus.

Too much, the Magic Bus

There is a somewhat darker or more disturbing account of what has happened in the evolution of human culture itself, a narrative that continues the arguments of the Situationists who insisted we were no longer really living in the modern world, but largely just consuming and spectating other people's images of reality.

Some worry that the alienation from physical, embodied life that came with literacy, machines, city-dwelling, and eventually telecommunications and broadcast culture is only made worse and more inescapable by the proliferation of all the virtual "realities" in video games, streaming media and cyberspace. Sometimes I'm one of those worriers.

We are encouraged to make ourselves part of The Spectacle now, and it's comparatively easy to do so. This is especially obvious with people who are interested in presenting themselves as Internet celebrities or "brands," but it's also true of any of us who doctor their photos and then post them on Instagram - even just choosing and posting photos makes us producers of the public spectacle. And we may not even feel we exist unless we are part of that mediated spectacle! In the early 21st century, we have been encouraged to think that attention via the media will provide power, love, transcendence, salvation, satisfaction, bliss. To be is to be seen, in this "attention economy." To be a success is to get attention – not so much for our embodied selves as for our media representations of ourselves. A lot of us are literally trying to become images of ourselves now, in order to "exist" more fully. We want to become media. Embodied life? That's not where it's at (to use another 60s idiom).

Your phone is a portal into this spectacle of human creation and mediation, but does it really bring you reality or bring you into other people's reality? What if the communication media are actually keeping us detached? Media is the plural of medium. A medium is something between you and something else. Maybe we rarely even get close to reality any more, when we are so focused on the media that claim to represent it to us, but which maybe also always screen us from it?

Hyperreality: The Real Ain't What it Used to Be

One way our current situation has been explored is with the concept of hyperreality.

The term was coined by the challenging French intellectual Jean Baudrillard, and has been taken to suggest different things at different times by Baudrillard and his interpreters. Baudrillard is "postmodern" in that he does not ultimately believe we ever get to reality. Every attempt to achieve this realness is false, a simulation of reality. It is a representation of reality. As human beings, we live in representation, not in reality.

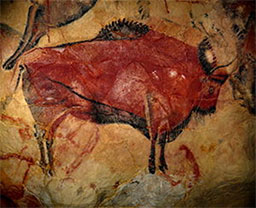

We always have, since we started drawing on cave walls or using language to describe the rich berry bushes we discovered on the other side of that hill. But you could say that maybe it is "getting worse," because we struggle more and more to nail down what is real, and that distinction is less and less obvious. Hyperreality is about the fact that human consciousness does not easily distinguish reality from a simulation of reality, and can accept mediated experience as at least as important as directly lived experience. This becomes more disturbing in societies where technologies present more and more realistic simulations of reality, and we spend more and more of our time with simulations of reality rather than with reality itself. Eventually, what we mean by "real" tends to become what is reproduced in media - a mass-reproduced simulation of reality. "Reality itself founders in hyperrealism, the meticulous reduplication of the real, preferably through another, reproductive medium, such as photography" (Baudrillard 1976).

Ever deepening hyperreality?

At one point Baudrillard proposed four stages of imaginary/symbolic representation – representation turning into what he liked to call simulation – in human culture. It may be helpful to think of these stages in very basic terms as following upon one another from the prehistoric period up to the present.

Before there was human culture and language and representation, presumably, there was a bison there in reality (for example). But we can't talk about or understand the bison except in representation. If the bison is trampling you, maybe that's reality. But your story about the bison, your ideas about the bison, your image of the bison – that is always a representation, and the bison itself is no longer real (physically present, trampling you).

Stage One

Stage One

Originally, when we copied something, it was a copy of a "real" original. We painted a bison on a cave wall – it represented and reminded us of a real bison, which we would like to hunt down and eat (presumably – I don't actually know why cave people painted bisons on the walls). We probably agreed that the bison referred to something in the real world, though it was actually just a composition of colours on a cave wall.

Stage Two

Stage Two

As the world progressed, we started creating images and symbols that were not faithful copies of reality, but which still hinted at something "real" in our fantasies. Nobody has a penis that big, but penises do loom very large in some of our imaginations, as Freud and others have shown. The image points to, though it perverts, a "reality."

Stage Three

Next, the proliferation of imaginary symbols comes to mask the fact that what they refer to does not exist anywhere actual. The symbol may be only a word, since there is no physical original to copy. We have a word for God and a word for justice, but these words may not directly represent any thing that is or was actual, physical, real in the earlier sense. If we try to represent God or justice we can at best use a metaphor or something physical to suggest what we feel about these things. That is because they are not real in the same sense that the bison was real. Our feelings about them are real, but are they real apart from our feelings?

Stage Four

Finally, we are happy to copy and symbolize the copies and symbols themselves; there no longer needs to be an "original," a real-world referent, or a material thing or physical being that corresponds to the copy. Copies of fictions are just as easy to work with as copies of real things. We come to inhabit this world of copies without originals. That is what human culture is. A matrix of "real simulations" of made-up, simulated unreal images.