Fake IDs

Consumers of social media are often very focused on the "fakeness" of how people may represent themselves online. Whether it is catfishing on dating apps or the framing, filtering, and staging of photos and stories by Instagram users and influencers, many people think it is disappointing or inauthentic if people's online images don't accurately reflect their embodied identities offline. Still, all of us, even the most honest and sincere of us, edit ourselves for social media in various ways. It is media, not spontaneous presence in the world (though I'm sure we "edit" that too). I think this is probably a new thing for most humans: to be able to present themselves in an abstract public "space" as media and even interact "socially," as media. It's a new mediation of the self different from our bodies, our verbal and non-verbal communications to other present people, or even our photos albums, our words written down; and I've tended to think that it lends to some of the feelings of derealization that hyperreality means or implies. Suspicion about the truth and authenticity of our experience, more and more of which is mediated by images and technology.

As we'll look at shortly, it may not be so much that our online identities are derealized, as that they are a new hyper-public kind of identity formation, that has never been possible for so many people before. The media are now a "space" for identity formation, in a way that only used to be possible for a few famous people, celebrities, and media personalities.

Hanging with some friends last New Year's Eve, before I had my Covid beard.

In what ways can an online identity be "fake"? It seems simple-minded to me to complain that "social media is fake," and then lump catfishers and frauds together with influencers, gamers, and your grandma's picture of her dog wearing a hat. Despite how complicated and confusing it all is, I would suggest there are degrees of "fake identity" on the Internet, and most of us are fairly aware of this.

All media is "fake" in a sense: it is representation. Media is not living and breathing flesh. Packaged, pre-recorded media is not spontaneous present life; how one represents oneself can only be real up to a point. But the mediated versions can all be closer or further from embodied spontaneous identities depending on the media, the person, the intention of the person, and the conventions of the medium. To me there seems to be a spectrum of the relationships possible between people's online media personalities and their embodied spontaneous personalities, and really I think anyone who is paying attention will actually have typical expectations for how closely different kinds of online personas should correspond to the offline ones, based on the medium, the given personality, and the "genre" of the platform or account.

As touched on briefly in Lesson 3, electronic media in the 20th century mostly came down to a simple unidirectional push from producers to consumers. Producers (professionals backed by corporations or in some countries by the government) made media which was then more or less passively received by consumers. The internet disrupted that model fundamentally, but many vestiges of it remain online. Many people today are both producers and consumers of media. (Do you have an Instagram feed to which you've posted at least one image? You’re a media producer!) The fictionalizing, sensationalizing, glamorizing, and performative aspect of mainstream American broadcast media from the 20th century has been largely adopted or adapted by many social media personalities. Meanwhile less premeditated sharers are simply “performing themselves” online, perhaps a bit more like reality tv contestants (or the earliest ones anyway), and sometimes even more artlessly than that, more just like someone showing you pictures of their baby they carry around in their wallet - not a lot of performance or "spin" or production values or thought gone into the "product." Not a lot of premeditation. (Though they put the cutest pic of their baby in the wallet.)

I think different platforms lead to different expectations from the audience. You might not agree exactly with how I've ordered things here, but you should be able to see what I'm getting at:

At the authenticity end we have basic peer-to-peer communications - phone calls, texts, DMs in apps. If you're texting your IRL friend, they can expect you to be representing your offline self in what you write. If you tell someone in a Tinder message that you are six feet tall they can have a right to believe that you will really be six feet tall when they meet you in person. I've put TikTok before YouTube here though I have relatively little experience on TikTok because it seems to me that a frequent stylism on TikTok is to at least look like things are happening somewhat spontaneously and at random, like real life. Often people fall down or have other fails that seem like reality itself. YouTube influencers are almost always more polished and produced looking, anyway. (At least what I have watched tends to reflect this.)

Nathan Sosiak, who took this course in 2023, questioned my placement of LinkedIn so close to the authenticity end. My point was that people looking to work with you are going to assume/expect that you match your presentation there when they meet you in real life. But perhaps that's so naive that it doesn't even match users' expectations anymore and they see that as a platform particularly likely to be bent by "marketing," spin, and even downright lies.

In terms of what it is reasonable to expect from social media producers when it comes to fidelity to their offline identities, I sometimes think it is worth dividing up the online presentations of self into different categories. For instance, just as an example, we could identify communicating, sharing, gaming, commentating-influencing and lifestyle/performance-influencing.

Obviously this table could be expanded with all sorts of other categories and nuances within the categories shown. It is mostly meant to suggest that there is a range of contexts and expectations of authenticity online, though at times we may not keep them all straight in our heads, because there is so much flattening and intermingling of these contexts on our platforms and devices.

If someone is communicating we hope and expect them to represent themselves honestly. This is why catfishing is bad, just as is texting your partner to say you are working late if you are actually with another lover. In communication, the expectation (or at least the hope and demand) is that you are representing yourself authentically.

Similarly, with sharing. It is a more "public" (not directed at a particular person) act than direct communicating, but it is often done mainly with friends and associates you know offline, and we assume that offline-you is meant to be represented accurately in what you share, though in a partial and edited way. If you share a post about Black Lives Matter or a picture of your cat, there is an assumption that you mean it, or that it really is a picture of your cat. You can get in trouble and lose credibility if things prove otherwise.

With gaming, the situation seems more complex. Online gaming is virtual reality (not hyperreality), so it starts from the assumption that things aren't real - it's "only a game" (though last week's lesson might make you think twice about that!). Your avatar is not your self, and personalities are recognized as players. While that term has come to be used slangily for manipulative people (not playing the game, but "playing" other people, like instruments), to be a "player" also refers to the unpremeditated free play of children as well as to the "serious" but still supposedly all-for-fun competitiveness of sport, and to the intentional masquerade of the theatre, intended to be "fake for entertainment." If something is play, we tend to expect it not to be real in important senses. So we don't expect players to pick avatars that look and act exactly like their embodied selves. Games are an area of free play (though as Stacey Goguen showed, we can't always treat them as having no real-world ramifications). So here "authentic representation of yourself" is not necessarily expected (or even desirable), despite the fact that sometimes people do actually end up feeling most fully themselves in those play environments. They let their embodied social guards down, from behind the safety of the avatar mask.

Commentators are a kind of influencer that tends to be very focused on something other than themselves. Social and political commentary, reviews of the arts, discussions of philosophy or history or trends. I think one expects them to represent their true offline identities accurately, and they can be "canceled" as individuals for the things they say about others, the world, society, politics, the arts etc. They may be performing for the camera in a sense, but we hold them accountable for their words and identities.

Performers (or self-performers) are what I am calling lifestyle and performance influencers who are focused on themselves and their lifestyles or careers or artistic endeavours as the product. I'm thinking here of exclusively social media influencers, not mainstream corporate celebrity influencers like Kylie Jenner or Ariana Grande. Most of these new 21st century online celebrities are bending the genre of social media sharing in the direction of commercial media performance. Here it seems somewhat naive to expect people to be presenting their offline selves, though they certainly might be, and presumably usually are at least to some extent. Like reality tv, they are performing their lives. Consumers often gravitate to them for the same reason they do mainstream celebrities, because they want (not entirely real) mentors, someone to idolize or emulate, or wish they had friends like that and could learn to be more like that themselves; they serve "parasocial" roles for some people (see Lesson 3); you can feel like you're hanging out with them, even though they are also larger-than-life celebrities, because they are media. The culture of influencer celebrities seems to me like an extension of reality tv: real people "performing themselves" as semi-fictionalized characters. Are they "being themselves"? Don't we actually want them to be "larger than life"?

The self as Spectacle. These are idealized and edited versions of life and probably of them, so "not real" in some important sense. But at the same time - like the performers in porn or the contestants in reality tv shows - they also really are those people at least in some sense and really are doing those things, even if they are doing them in front of a camera. So in a sense what we see is both real and simulated: hyperreal. Consumers of their media may complain that these images of real people are "unrealistic," but they continue to consume the images, partly because they aren't realistic, but rather consumable fantasy.

I'll come back to the relationship of the person to the media persona in terms of "curation" in the next section. The basic idea is that the person represented in the video or images is a creation or presentation of the person behind the images, a media producer, with all of the fictionalizing, and branding, etc that were part of 20th century manufactured media - and there's nothing wrong with that, as long as you understand that it's media and not reality. YouTube vlogger Alice Cappelle considers lifestyle vlogging as a "deal" similar to that between audience and creator in a movie theatre. We have agreed to meet in an unreal but emotionally satisfying "collision." She suggests that these hyperreal, parasocial kinds of media should be seen more as therapeutic art than spontaneous social interactions - or rather, she concludes that social interactions themselves may not revolve around authenticity so much as around this kind of emotional therapy and imaginary bonding:

... the exchange between a viewer and a creator is similar [to] that of a patient and a therapist, except that the experience and stories shared by the vloggers are as therapeutic for the audience as it is for themselves. [This] brings us back to the initial metaphor of the "deal": a movie, a book, a vlog is a place of collision of two imaginaries. The bond the creator and the viewer share is not based on authenticity, but on the emotion produced, crafted by the vlogger. In the end there is no such thing as authenticity. Just look for a second at the friendships you have in real life. We constantly edit our thoughts to make them fit social norms, social codes - to appear friendly, intellectual, intimidating. We all lie sometimes. and we behave differently depending on the people we're surrounded with at that precise moment. The result is that we are always unsure of what our true self is, which version of our self is the most sincere. For me, watching vlogs and bonding with vloggers has been a way to just escape for a bit, to discover a bit more about myself, and to project myself as well. It really feels empowering. (Cappelle 2021)

But of course Cappelle is a vlogger herself; she knows well the imaginary power of this kind of "interaction." Many viewers, rather than treating the vlogs as self-extending fantasy/therapy/escape, instead feel disempowered when their own real lives compare badly to the lives portrayed by their social media "cohort." We think that "this is what our life could be!" but never see the tedious aspects of the lives, the work that goes into that 20 minutes, the times they got their makeup wrong and had to re-shoot, the stress and burnout. The ways in which, even if they are being spontaneous and real, they are also always acting for the camera.

When the rest of us treat social media personas as our parasocial circle, we may well feel supremely inadequate, like the fat kid outside the high school clique (that was me!). If you think high school is a bitch, wait till you get on Insta and Tik Tok and Twerk (or whatever it's called). Now you're trying to fit in with semi-professional influencers who spend all their energy in presenting a larger-than-life identity. People didn't worry quite as much in the past, I suspect, (though some did) about not living up to the cuteness and wittiness of the characters on Friends or even not being able to keep up with the Kardashians, because on some level television was still acknowledged as not real life, fictional, staged, scripted, out there, made by giant corporations in Hollywood dreamland - not anything that could be confused with socializing with real people. Chapelle encourages us to see vlogs today in the same way, and not to worry about the parasocial escape some people are replacing embodied friendships with. Escape is therapeutic.

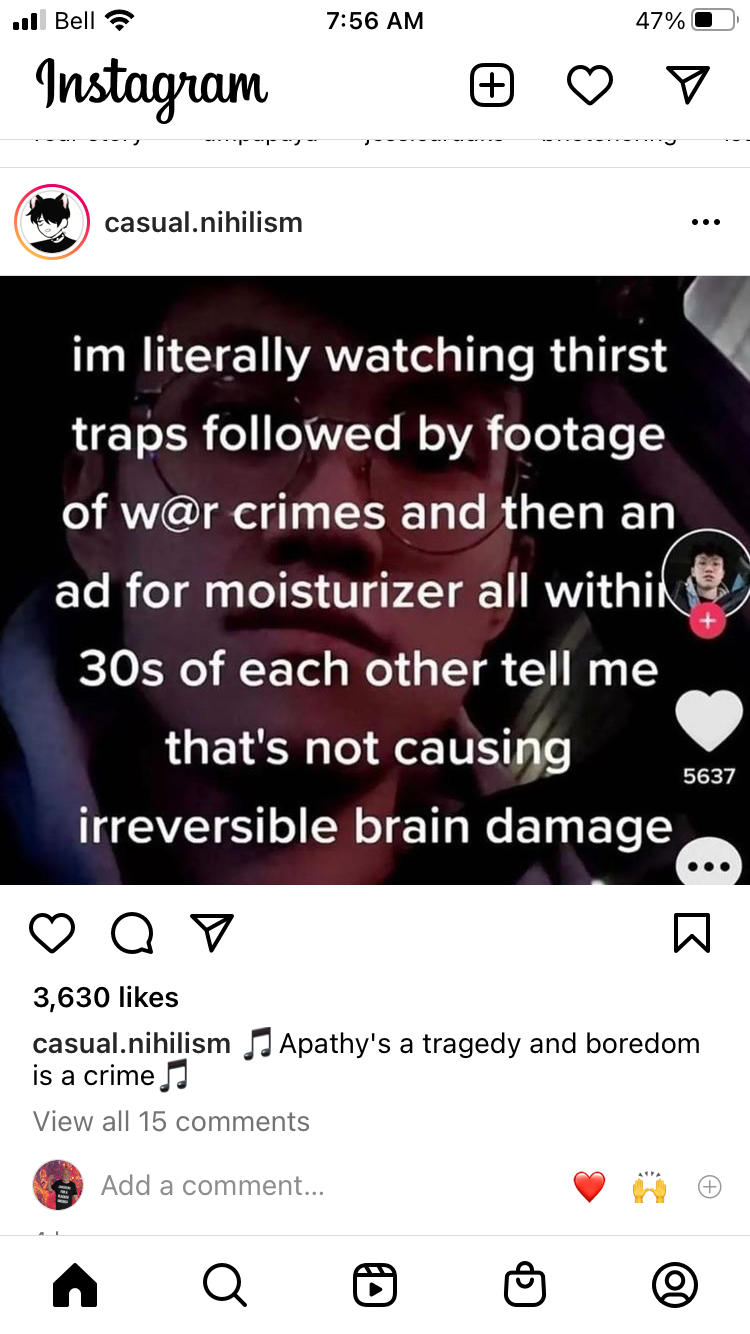

Social media is only sort of social. It is not social in the sense of being interactive spontaneous engagement with others most of the time. And much of it is not even about connecting to other individuals or groups, actually being social (remember Siva Vaidhyanathan's title Anti Social Media reminding us that there are at least some things about consuming media that make it anti-social). What the major social media platforms tend to provide is a mediated mix of everything: social connection with people we know, glimpses of other people's reality and fantasy, news, political views, corporate media, edited photos, ads, absurdist videos, fiction, heartfelt activism, whacky escapism, oversharing, genuine communication, lies, fake news, and stuff your real-life friends really wanted to share with you. It is television plus us (and them) - exponentially. All presented in much the same way. No wonder we don't know what is real any more.

This partly also ties in with our continued television era readiness to accept any media as escapist entertainment. But now we are socializing and engaging in political action and communicating with our friends and families and strangers through our entertainment media. Media has thus become even more of a hyperreal mix of serious, heartfelt, ironic, duplicitous, authentic, personal, shared, fabricated, manicured, raw, funny, heartbreaking, real and fake media, just like tv was only much more so.

So what does it really mean to say an online identity is "fake"? Don't we often crave the fake? Maybe it's always actually the simulations that we want, not real people, and we want to be simulations ourselves now, to get all Baudrillardian about it. Is it great that our identities and our social lives can now be just as unreal as the rest of our mediated Spectacle? It seems to me that it's a case by case question, rather than something to make a sweeping statement about.

Thanks for reading, as always. LOL