Information vs knowledge vs understanding

Larry Sanger is the co-founder of Wikipedia, a site that is a prime example of the extended mind. Sanger startled some fans when he came out with an argument against the de Lange kind of thinking in a 2010 opinion piece.

Unlike Robin de Lange, Sanger has come to question the increasingly common view that commiting knowledge to memory is an outdated aspect of education and intelligence. He also has concerns about our increasing reliance on some kind of "hive mind" (joining in on the thinking process somehow with a bunch of other people networked together) and on education trends that promote the benefits of collaborative learning online as the successor to the old-fashioned classroom model featuring a "sage on a stage" (me) and each student confronting the knowledge that the "sage" imparts as an individual, on their own (you).

Educationists inspire us with the suggestion that collaborative learning online can serve as "the core model of pedagogy." Knowledge is primarily to be developed and delivered by students working in online groups. And finally, the co-creation of knowledge can and should take the place of reading long, dense, and complex books. Such claims run roughshod over the core of a liberal education. They devalue an acquaintance with (involving much memorization of) many facts about history, literature, science, mathematics, the arts, and philosophy. Such claims also ignore the individual nature of much of liberal education. Reading, writing, critical thinking, and calculation, however much they can be assisted by groups, are ultimately individual skills that must, in the main, be practiced by individual minds capable of working independently. (Sanger 2010)

Wikipedia co-founder Larry Sanger - just a backward old boomer now? Or sending a much-needed warning about the serious unintended consequences of the world he helped create?

As may be clear from the passage above, what Sanger is above all concerned about losing are the values that a "liberal education" was meant to promote. This is something other than job-training or skill-acquisition, or even problem-solving. The values he is concerned to preserve (part of the humanist tradition and arguably the legacy of print culture as discussed in lesson two) might be summarized as follows: individual thinking and patient reflection, listening to opposing views before coming to one's own conclusion, gaining personal knowledge of a reliable kind before acting or making decisions, and taking personal responsibility for one's opinions and decisions, which are reached through logical consideration of one's internalized knowledge, through rational debate with others, and through time-consuming inner reflection.

Many other critics have worried that the Internet itself, by making information so cheap, is serving to devalue knowledge. And that people no longer have as much of it in their heads. Some think if we don't know much in our meat minds, we can't really be said to be very educated.

This begs the question of what educated means (and whether most people can afford to be educated in our world), but the belief in personal knowledge can be hard for someone raised in Sanger's privileged world of liberal education to let go of. Myself included.

Back in the day ...

In my own experience as a teacher in the liberal education tradition, I have noticed some trends in how students have been evolving. Some of the ways the students I teach today seem different from those I taught in the 20th century are clearly related to the Internet and the attitude toward knowledge that the extended mind model suggests. I offer this personal anecdotal impression for what it is worth.

I find that students today are generally better at writing than they were 15 or 25 years ago. On the other hand, typical students (not most of the ones in this class, obviously) can find reading with focus a real challenge or so unpleasant that they avoid it; or they may just think it's inefficient because of the time involved (how are you doing with this lesson? Still reading?). If students on average write better than they used to but don't read as carefully, it would make sense, because the Internet requires much more reading and writing than watching tv does, but most of what we read online is fairly quick-and-dirty, sometimes just headlines or pull-quotes, and no one is going to quiz us on it.

I'm not actually sure that anything has changed. There have always been people who didn't or wouldn't or couldn't pay attention and concentrate on reading, particularly schoolwork. And obviously many people today can still read things as long and complex as my lessons and understand them clearly and deeply (though perhaps not always remember the details accurately and well?). How well do you think you would have done on the midterm multiple choice if you hadn't been able to search up answers you didn't know? Whether an individual can do focused reading and remember what they read or not may be more a personal matter than a social concern brought on by new technology. But I think it's worth at least thinking about the arguments of people like Nicholas Carr, discussed below, before completely dismissing their worries about "the death of the book." One new question is whether people retain anything in their meat minds, since we are so used to knowing where to find it if we need it.

Students today may indeed be less likely to remember facts, names of people from the readings (do you remember who John Searle was?), or abstract concepts than they used to be. I do personally think it's at least possible that this is because focused reading helped people take knowledge on board in a more linear and interconnected way, forcing them to make it a part of themselves - a way that using the Internet perhaps does not. Our old friend Marshall McLuhan talked about this change from linear information (one thing after another, with clear connections) to "a nonlinear field" (random-access bits of information all vying for attention) in that clip from 1960 that I included in Lesson 3. If we don't retain information the way we used to, part of it is probably to do with the notion that we don't have to remember information in our meat minds any more: the Internet will remember it for us. Connecting bits of information to each other to create a story can be hard, and many people now see that as unreal: reality is a meaningless storm of noise, not a story that adds up). A final contributing factor is probably just plain distraction overload and TMI. When one is looking at one's phone during a lecture, or getting notifications from friends while reading an article, one is simply not focused and following connections if they are being made. Focusing, it has been shown, "turns on" the hippocampus, which is the part of the brain that acts like the "record button" for meat memory. If distracted while learning, one is unlikely to remember or understand much. That much I do feel secure in saying. from my own experience!

There is in fact a fair amount of evidence that humans of all ages are becoming worse at retaining information precisely and accurately, and this may have something to do with the easy access we have to information (and the fact that we have too much of it and don't know what is worth remembering). If you find you don't actually know the answers to a lot of the questions on my multiple choice quizzes, it might be worth contemplating why none of that stuff "stuck" in your meat mind (and what does lodge there instead?). Why does so much go in one ear and out the other, as they say? It certainly can't have been because you didn't find it fascinating at the time! ;-)

Getting stuff lodged in your meat mind makes new stuff that comes along more meaningful and interesting, even in a limited context like this class. This course does have a narrative arc of sorts and involves internal allusions and references just like a good novel or rap song. New lessons often build on foundations from previous lessons. If you never really understood what I was getting at when I discussed hyperreality, for instance, then when I refer to something as "hyperreal" in a later lesson, what I say won't make sense to you and you'll likely just ignore it. If I foolishly assume that you have everything I have told you already safely tucked into your meat mind, I might say something at some point like "I think of myself as a kind of a poor man's Noam Chomsky." Some people will have known who Noam Chomsky was before they took the class, and a few may remember what I told you about him and what he had to say in a video from Lesson 3. If not, you will not know what I am saying about myself, nor will you be able to enjoy the bit of ironic humour in the way I have said it (Noam Chomsky is an advocate for the common people, in his way). The more attention you pay, the more you know and remember, the more interesting things are; and I tend to think that the more you take on board as you go along, the more meaningful new things become.

Am I leading up to saying in a doomer boomer type of way that people are dumber today because they don't read books and memorize things, and now rely too much on extended minds? Certainly not! If anything, I feel like people generally come across as "smarter" in the 2020s than they did in 1995. They are more open-minded, more aware of the diversity of thought and human experience, generally quicker and usually slightly more awake than those tv-watchers I taught "back then." I'm not convinced that average intelligence (whatever that is) has changed in any way. Basically, like books or even television, the Internet is a medium - a tool - and intelligence depends on how the user choses to use the tool. To paraphrase something said a long time ago by the philosopher Lichtenberg: the Internet is a mirror; if an ape peers into it, no apostle is going to stare back out at him.* (No offense to our primate cousins! Chimps may actually be much better at remembering than humans are, it turns out. See Chimp vs Human! | Memory Test | BBC Earth.)

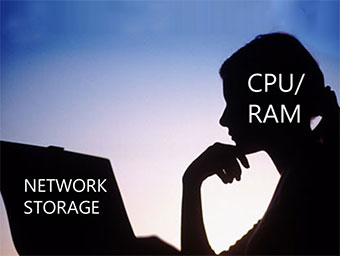

Our tools don't have to shape us beyond our ability to make choices and decisions; we can choose how to use books, television, or the Internet. But. That doesn't mean that the medium of the Internet doesn't invite or encourage certain kinds of thinking and make other kinds more difficult or unnecessary-seeming. It has encouraged an attitude toward thinking where individuals see themselves as a kind of CPU, and the "data" is kept in the cloud until needed for short term "processing." I've heard many people describe their relationship to knowledge in terms like this: "I can't process that information right now." Well, we are not really information-processing machines!

As technological tools evolve, it seems to influence human beings' view of what we are, and how we work. In medieval Europe, Christians still saw themselves as images of God, potential angels. During the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions, they started to see themselves as complicated machines. In the 20th century, they were encouraged to view themselves as "consumers" (and that continues, of course). Today, perhaps, we imagine we are a kind of computer, the forerunners of AI. Rather than thinking in terms of wisdom, understanding, or knowledge, we may be focused on the basic coinage of information. But information is easy and dirt cheap now. It shouldn't be your focus. (Though you still might need to have some of it onboard.)

Information, knowledge, understanding, wisdom

At the risk of sounding condescending, I'd like to get even a bit more Old School on you for a minute. I would ask you to consider possible differences between the concepts of information, knowledge, and understanding. I like to define these terms as follows (and test people to see if they've understood and remembered my ideas accurately on quizzes!):

- information is facts or data, without context or understanding;

- knowledge is facts and data with enough connections to other contextual facts and data to be meaningful and feel like you know something;

- understanding is knowledge of facts or data in context and with the kind of informed, context-aware, perhaps even empathetic appreciation of the facts or data that allows one to explain them to someone else, apply them, care about them, and do things with them.

For example, consider this factoid:

Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote "The Letter from Birmingham Jail" in 1963.

This is an example of information. You could memorize it or look it up online, but it doesn't mean anything on its own.

What more would be required to make this into knowledge, and what in turn would convert the knowledge to true understanding? Understanding is knowing information in context. I ask you to consider whether without having knowledge that is already in your head (as opposed to knowledge that is sitting on Wikipedia or some class notes somewhere), information remains meaningless. It may be memorizable, but it is unmemorable.

Those who express reservations about the Internet as a tool of knowledge, often do so because they are afraid that it will invite our species to dispense with the humanist values of individualism in favour of dispersed collaborative knowledge and decision-making - a kind of intellectual Division of Labour that impoverishes the commitment of the individual to full understanding and leads to irresponsible thoughtlessness on most people's parts. They are afraid that individuals will grow used to plucking quick and facile factoids from the web, and piecing together broad but shallow semi-understandings of things. Nicholas Carr in a famous, flawed article called "Is Google Making Us Stupid?" (2008), was one of the first to raise these concerns to the level of public awareness.

Carr thought that focused reading, like we did with books before the Internet came along, led to deeper understanding, and also trained our brains in forms of thinking that he considers important to his conception of the human being. In a briefer version of his ideas published in The Wall Street Journal in 2010, he talked about research that seemed to support his worries.

In an article published in Science last year, Patricia Greenfield, a leading developmental psychologist, reviewed dozens of studies on how different media technologies influence our cognitive abilities. [...]

In one experiment conducted at Cornell University, for example, half a class of students was allowed to use Internet-connected laptops during a lecture, while the other had to keep their computers shut. Those who browsed the Web performed much worse on a subsequent test of how well they retained the lecture's content. [...]

Ms. Greenfield concluded that "every medium develops some cognitive skills at the expense of others." Our growing use of screen-based media, she said, has strengthened visual-spatial intelligence, which can improve the ability to do jobs that involve keeping track of lots of simultaneous signals, like air traffic control. But that has been accompanied by "new weaknesses in higher-order cognitive processes," including "abstract vocabulary, mindfulness, reflection, inductive problem solving, critical thinking, and imagination." We're becoming, in a word, shallower. (Carr 2010a)

A year later, there was some more urgent boomer doom of this kind from Jaron Lanier. Lanier is one of the originators of virtual reality technology itself. So, like Wikipedia's Larry Sanger, with which this section started, he is a critic of digital technology from within the culture, as you might say. Lanier made another book-length appeal for the value of the individual to continue to practise undistracted traditional print-culture-style reading, finding time for personal solitary reflection, and engaging in informed civic debate and decision-making by traditional means. This was in his 2011 book, You Are Not a Gadget. More recently still, some of these worries have been updated to include the affects of AI on human intelligence in Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic's book, I, Human: AI, Automation, and the Quest to Reclaim What Makes Us Unique.

Albert Bartholomé, The Artist's Wife Reading (1883)

Many social critiques have drawn attention to the paradox that never in human history has the average person in the developed world had access to so much information, and yet (supposedly) never in the last 100 years or so has the average "educated" person in North America been so ignorant of things like the facts and timelines of history, the meanings of "big words," geography, science, non-pop culture, or other stuff about the world that one was supposedly learning in school "back in the day." If that's really true, there is probably a correlation. The Internet makes us painfully aware how much there is to know and how little each of us actually knows, or can know. This may make it seem futile to try to take any knowledge on board (in our meat minds), and may make it hard to decide what information we should keep there, when we can always find any "information" in our "extended minds" if we need it.

The distracted and cherry-picking way we have of reading or getting information online might also contribute to this. Carr started his investigations into how Internet use affects intelligence because he found himself becoming more incapable of remembering things and thinking deeply about them as he started using the Internet more. He didn't use these words, but you could argue that what he was saying was that his constant use of an extended mind had a negative impact on the functioning of his meat mind. I have noticed some of these effects in my own meat mind as well.

* Lichtenberg actually said "books," not "the Internet." He lived from 1742 - 1799. He was famous for one-liners. Another one was “When a book and a head collide and a hollow sound is heard, must it always have come from the book?”