Mobilizing real-world political action and democratic resistance through technology

Whatever we think of the results of online activism, it is fairly clear that the explosion of digital technology has had an impact on the speed with which news and ideas can be spread. It has also created new means for the organization of embodied political action - for good or evil.

In her 2018 study Twitter and Tear Gas, Zeynep Tufekci talks about how unorganized slactivism on its own can lead to movements that peter out without real effect. One of her key examples is the 2011 Occupy movement that hit the United States largely as a result of the 2008 financial crisis. This was the movement that started pushing heavily against "the 1%" - the tiny elite with so much of the wealth and power in America, and whose greed and manipulation of the system seemed to be responsible for the heavy losses of so many average middle class Americans in that crisis. The Occupy movement was partly a social media-driven phenomenon, inspired by the collective efforts of "Arab Spring" in Tunisia and Egypt (2010-11), where use of technology had contribued to revolutions that were considered to be at least initially successful.

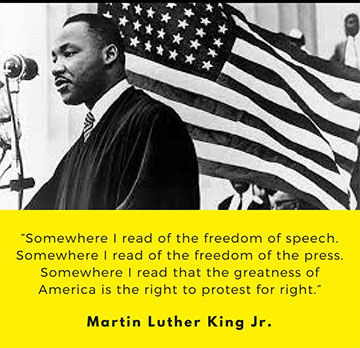

Tufekci warns that today's "pop-up" protests and revolutions are different from the organized resistance that happened before smartphones and social media. The 1963 March on Washington in the American Civil Rights movement that culminated in 250,000 people being congregated to hear Martin Luther King, Jr.'s "I have a dream" speech was a carefully coordinated effort that took six months to plan and realize, and was part of the larger Civil Rights action that had already involved eight years of organized and unrelenting physical, hard, sometimes fatal public action (although the broadcast media of the times were certainly a huge part of making the effort as successful as it was in the end). Tufekci looks at some of the ways in which the initiators of the Gezi Park protests in Turkey (2013) - at most of which she was personally present - were not entirely prepared once the government showed itself willing to negotiate, because of the spontaneity of the uprising. Tufekci suggests that social media mobilization without understanding of the real organization of power and the institutions one is trying to change can easily fail: "The internet [...] allows networked movements to grow dramatically and rapidly, but without prior building of formal or informal organizational and other collective capacities that could prepare them for the inevitable challenges they will face and give them the ability to respond to what comes next" (Tufecki 2017). Thus, a movement with a background in political opposition, deep understanding of "the enemy," and ability to respond with something other than a pop-up mob - a movement like Black Lives Matter, for instance - may have more chance of making real change happen (excruciatingly slowly and painfully as usual) than a spontaneous uprising of privileged disgruntlement like the Occupy movement. Tufekci's book is too nuanced to make a quick summary, but I highly recommend it if you are interested in activism and how technology and social media can be leveraged in it - and what to watch out for.

Smart mobs are dumb

Unfortunately, social media can be used by people whose motives we don't approve of to organize real-world action as well, sometimes creating undeserved violence and disruption through the spread of disinformation. In a 2018 article in Wired, Timothy McLaughlin examined "How WhatsApp Fuels Fake News and Violence in India." The article tells a shocking story of the brutal murder by beating of five innocent men in the small village of Rainpada, India. The men had come to town for the weekly market, but when they offered a bit of food to a young girl from the town, villagers seem to have feared they were one of many rumoured "bands of kidnappers roving the area and infiltrating villages to snatch young children."

Narmada Bharat Bhosale's husband, Dadarao Shankar Bhosale, was killed by the mob in Rainpada. (Photo: Prarthna Singh) (from the McLaughlin article"

These rumours were being shared on the platform WhatsApp, and included a video showing "pale, lifeless children laid out in rows, half covered with sheets. A voiceover warns parents to be vigilant and on the lookout for child snatchers." McLaughlin goes on to explain: "The photos are not fake, but they don’t show the victims of a murderous Indian kidnapping ring either. The pictures are of children who were killed in Syria during a chemical attack on the town of Ghouta in August 2013, five years earlier and thousands of miles away" (McLaughlin 2018). In other words, the rumours being circulated on WhatsApp were at least in some part unsubstantiated and sensationalist "fake news." They incited fear, and in this and other incidents in India discussed by McLaughlin, violence:

Starting last spring, the platform began being linked to incidents of mob killings, most of which fit a similar pattern: People deemed to be “outsiders” were targeted by large mobs accusing them of being child kidnappers after rumors to be on the lookout circulated on WhatsApp. Some of these false rumors appeared in the form of highly convincing doctored bulletins from local police; others used the photos from Syria and manipulated videos.

It isn't clear from the Wired article what the motivation of those creating and sharing the rumours actually was, but it's clear that the effect was to cause or fan fear and hate, and eventually led to several terrible deaths. The Indian government demanded that WhatsApp address the problem, which it tried to do in several small ways, partly (according to the Wired article) because it is very interested in expanding its market in India.

As with all situations involving the spread of hate or fear, incitement to violence, and simply disinformation on social media platforms, this is a new problem we are experiencing with a still very young medium. The corporations that run the platforms would generally like to remain neutral and not have to take responsibility for the media they are facilitating. What should be expected of the platforms, and who exactly should police them, remains a topic of hot debate in India and presumably everywhere else in the world now.

Social media can as easily be used to organize politically for action by Black Lives Matter or White supremacists. In a democracy, it could be argued that freedom of expression demands that any organization or incitement to action that is not explicitly an incitement to violence should be allowed. But what people do with information and how mobs behave once they have congregated can make it hard to know what the role of the managers of the platform, police surveillance, and so forth should actually be. Your "people's revolution" may be my "fascist uprising." Lives are at stake.

In Canada, we have anti-hate speech laws that can be invoked if freedom of speech seems to be leading to incitement to racism, violence against women, or any other form of discrimination-stoking or targeted hate. When rioters stormed the U.S. capitol building in an attempt to disrupt the confirmation of Joe Biden as the president of the United States, involving many injuries and the deaths of four rioters and one police officer, the involvement of The Proud Boys in the insurrection led to calls here in Canada to declare the organization a terrorist group, and on January 25, 2021 the Canadian House of Commons did indeed adopt a motion by unanimous assent designating the Proud Boys as a "terrorist entity." The group was also, like Donald Trump, "de-platformed" from mainstream social media, including Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube. Lovers of free speech - even if they are not white supremacists - may feel this is the narrow edge of fascism, a denial of freedom of expression. Is that part of democracy that must now be discarded, or heavily revised as it has been to some extent in Canada and other democratic nations?

Motadel (2011) takes us through a history of revolutions from 1776 and the French Revolution up to the present, showing how the turn-around time between one insurrection and the next has shrunk exponentially with the growth of instantaneous global interpersonal communication, culminating in the TV-age domino effect of Tiananmen Square-Berlin Wall-Soviet collapse (late 80s) and the seemingly "viral" wildfire of the Arab Spring (early 2010s): "Drawing on satellite television, mobile phones and the Internet, the Arab revolts spread in weeks. Within seconds, revolutionaries send their messages against tyranny around the world. Unsurprisingly, dictators today feel uneasy about social media websites like Facebook and Twitter" (Motadel 2011, 4).

It's hard not to feel excited by the power-to-the-people potential of a universally networked world. But what we have had to face is that democracy means the people we don't agree with too. Do I really want democracy or do I want social justice? Don't make me choose. But maybe I have to.

So apart from the darker potentials of totalitarian surveillance that we looked at last week, there is another frightening side to networking technologies. If they make it much easier for the righteous to organize mostly non-violent insurrection, do they not also hold out the potential for coordinating evil action on an unprecedented scale? We know that there is a robust white supremacist community online, as well as organized misogyny, transphobia, and so forth. The dangers are not just their ability to spread and normalize racist and sexist ideas and agendas, but that they can coordinate "rebellions" of their own more easily through the tools provided by global networking. Meanwhile, there is still the question of Freedom of Speech and Democracy on the line here. You and I might both agree with suppressing the ideas of the Proud Boys, but can a true "democracy" still be said to exist if their hateful views are suppressed through governmental and corporate force? What if The Proud Boys were not a white supremacist and misogynist (and presumably also homophobic) group but instead, as was amusingly suggested when gay men hijacked the hashtag to disrupt the group's spread online, The Proud Boys really were a gay affirmative group - but in Russia, and the Russian government pressured its social media platforms to suppress the group because it didn't approve of their message? Many of us would be outraged. Can free speech and democracy really be reconciled with the fight against discrimination and hate?

Lane Jenning (2003) suggested that the wonderful potential of digital technology to foster virtual communities could just as well be used to assemble what Howard Rheingold has called - apparently in a merely coincidental pun on "smart bombs" - "smart mobs," that is, people bent on violence or crime and who can now act not as an erratic bunch of unconnected hooligans but in an organized fashion, coordinated through instant messaging and related technologies (arguably, we saw this with the U.S. capitol incident). Jenning cautioned: "The line between democracy in action and irresponsible disruption is unclear at best, and new technologies are never guaranteed to serve the public interest" (Jenning 2003).