Hyperreal politics: Manufactured media and democracy

In the lesson on the Global Village, I briefly mentioned Neil Postman's influential book Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business (1985). That book was a study of how the manufactured mass media in North America tend to turn everything into entertainment for a passive consumer, and the negative ways this might impact the democratic process.

Looking at this as an "outside insider," the great African American writer James Baldwin suggested that America's addiction to escapist media actually stands in the way of making America what it wants to be. It is a narcotic distraction from political and immoral realities:

It's alarming to reflect on how quick people may be to accept a make-believe just and happy world on tv rather than making that world a reality IRL (in real life). Nowadays, they often manage to enjoy a make-believe dystopia, rather than fixing the dystopia they are actually living in.

Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business

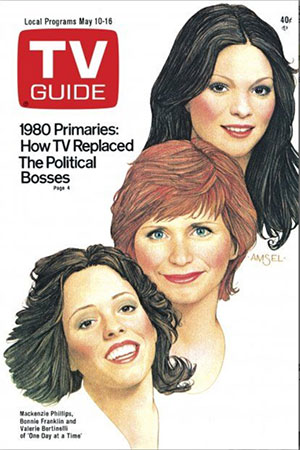

Neil Postman published Amusing Ourselves to Death in the 1980s, before the Internet. The most common and popular way for people to learn about the world at that time was through television, the manufactured medium of which James Baldwin was so critical. Postman thought that the focus on entertainment was a dangerous political change from the world before television, when most people had to read to find out about the world – books, magazines, newspapers.

The medium of print, as Postman saw it, conveyed the complexity of reality better than television. Reading forced a person to participate actively in making sense; it forced them to use their imagination and to think and spend time understanding. It forced them to pay attention and presumably take what they were reading more seriously.

Television, on the other hand, as discussed in the lesson on the Global Village, shows you reality in a way that books and newspapers can’t; but what it shows you is always a highly partial, edited, packaged quick slice of "reality." The people who make television are largely focused on entertaining you, not informing you, not making you think, or giving you a full argument or multiple points of view. They are also, primarily, at least in North America, focused on making money. And to do that they know they have to keep you entertained. Since we receive the news of real things through the same medium and packaged in much the same way as we receive drama, comedy, far-fetched fiction, parody, satire, comedy, and mindless entertainment in TV shows, it may encourage us to see the real things in the news as unreal and as further occasions for entertainment as well. Television made unreal things look real and real things look unreal.

Many people followed Donald Trump's first election, for instance, as ironic postmodern spectacle. It was like an episode of The Simpsons (It was one!). Only the Trump presidency was not an episode of The Simpsons: it was real. Some people don't see that, don't care, or would argue philosophically that it's not real. They've never met Trump, for instance. "Trump" is mediated and packaged hyperreality.

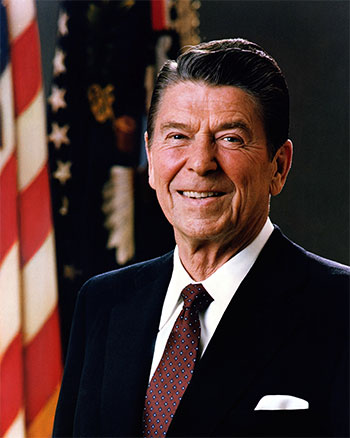

I remember when my grandmother told me she was going to vote for former movie actor Ronald Reagan and added "He's such a handsome man!" Reagan won, of course.

Television is focused on slick images, a fast pace, sensationalism and entertainment. Postman thought it often packaged even real and important things as entertainment, and this encouraged the audience to think of these real things as less real, more like the unreal things that made up most of what was on television - and to feel the same about them. Television didn’t make complete and logical arguments; it made "shows" or "ads" out of real life, even when it wasn't literally trying to sell you something. The programming, whether a sitcom, a political debate, or a news broadcast, is to some extent seen as "filler" by American corporate broadcasters. What they are focused on broadcasting is actually the ads, and the product they sell is actually the eyes of us viewers, sold to advertisers. (This model is also what commercial social media platforms have adopted, unfortunately I think.)

Television as a medium encouraged passive consumption of its media as entertainment, and the real and serious things it tried to tell people about started to be experienced as just more slickly presented images, just more entertainment. Reading stuff, paradoxically, had conveyed reality more fully than seeing images of that reality portrayed on television does. When reading a book, you had to think, analyse, understand, and see the complexity of reality more fully. You had to participate (through reading) and make meaning. (We'll return to this question of focused reading yet again in the Intelligence lesson.) What's more, it was harder to confuse the representation of reality in the book with reality itself. Video looks like a window on reality; a page of a book doesn't - or at least not in the same way.

Marshall McLuhan famously said "The medium is the message." What he meant in part was that we get a different communication depending on the medium we receive it through. "The same message" is experienced and understood differently depending on how we receive it. Adam Holzapfel, who took this course in 2021, drew attention to a classic example of this:

In the 1960’s political race between JFK and Nixon there was a televised debate and people who watched it on television believed JFK to have won the debate because he used makeup to prevent sweating, was more attractive than Nixon and overall, better composed when speaking. However people who listened to this debate on the radio believed that Nixon spoke and sounded better and therefore won the debate. This goes to show how much technology had an impact on election because if these candidates were only presented through radio Nixon would have won. (emphasis added)*

Reading a book, one perceives things differently than listening to it being read to you, or the same material in a podcast, or a YouTube video, or on tv, or in a meme. Each medium alters the message and how it will be received/perceived through the nature of how it communicates information.

Neil Postman had several hypotheses about the political effect of television on its audience; I have summarized some of the more important points below.

It’s true that we now have the Internet, a more interactive and potentially more realistic and creative way of getting at reality through electronic media. But the people of today here in Canada have had their expectations of the media shaped by the model of entertainment that television made normal; hence our "selfie" culture in which everyone wants to present themselves as a packaged media celebrity, and now real people's lives are treated as escapist entertainment as well.

Please consider carefully some of Postman's concerns from the 1980s about our entertainment-focused media (some of this will be a recap of things already said in the Global Village lesson).

Postman's concerns about politics and television

Mass media replaces complex ideas with simplified images. "A picture is worth a thousand words!" But is that really true? An image gives a powerful, but incredibly partial and emotional, glimpse of what is always a more complex situation. It’s fast and easy to see an image and get a message, but it requires no thought or consideration and focuses on a single emotional or aesthetic aspect of what it represents.

Mass media replaces positions with personalities. Positions (points of view that are open to argument, revision, and critique) require people to understand and think about them. It is easier to respond quickly and instinctually to a personality than to understand and reflect on a set of ideas. The mass media cater to this with the focus on celebrities and personalities (who are "relatable" and fun, or seem sexy or handsome or powerful or classy, etc), rather than ideas or policies (which are complicated and difficult and require thought).

One former student drew my attention to the 2010s example of UK Labour Party figure Ed Miliband, and how his physical appearance and the portrayal of it in the media led to him losing influence and credibility. As Wikipedia puts it:

Miliband was portrayed during Labour's 2015 election campaign as being genuine in his desire to improve the lives of working people and to display progression from New Labour, but was unable to defeat interpretations of him as being ineffectual, or even cartoonish in nature.[citation needed] Political illustrators perceived a resemblance to Wallace of the British animation Wallace and Gromit and greatly exaggerated this in caricatures; various images circulated in the press and online media of Miliband performing day-to-day activities such as eating a bacon sandwich, donating money to a beggar, and giving a kiss to his wife, all while displaying apparently awkward facial expressions. (Wikipedia, retrieved Jan 27, 2021)

Postman argues that most voters will not take the time to study and fully understand the parties and positions that the leaders represent. Instead, they often vote for (or against) the person (i.e., their media image), based on whether that figure has a "look" or personality that they like, or find impressive, feel they can trust, or seems like them. Appearance can matter a lot in our hyperreal media marketing reality. But behind the image are policies, platforms, programs for change or stasis.

Perhaps almost all politicians have become dishonest showbiz personalities, but I remind people that they usually do still stand for different values. It is dangerous to vote for personalities. This isn't Canada's Got Talent or a high school popularity contest. Rather than thinking about how Justin Trudeau or Jagmeet Singh "strikes" you, you should have a clear understanding of the policies their parties stand for.

Mass media replaces arguments with ads. A slogan like "Make America Great Again!" is an emotional rallying cry, rather than a plan of how the world will be affected. People are often happy to have their messages quick and easy and this leads to the tendency of the media to try to "sell" them things in the simplest and most one-sided way. Instead of a public discussion of goals and a realistic analysis of who will benefit and suffer, appeals are made at the most basic and unthinking level. Most of the public is also happy to have this quick way of deciding about a difficult and complex decision: loved their ad!

Mass media replaces active understanding with passive entertainment. As discussed in Lesson 3 and above, unlike reading a book – even an escapist fantasy novel – movies, ads, and television don’t demand anything from you in consuming them. You don’t have to use your imagination or try to understand what the author is telling you; you can just sit back and take it all in, uncritically and uncreatively. Or ignore it. Some people, like Guy Debord, argue that this leads to a view of oneself as a consumer and a mere watcher of culture. It discourages attention or involvement and, again, discourages thinking.

Mass media is too often escapist, distracting, fake, unrealistic, and exploitative.

So much television content is packaged escapism that Postman thought we had started to treat our news that way as well. Like fiction, it is generally about people we don't know and will never meet. In a certain sense, none of it is real in our own lived experience. All of it is packaged and mediated through a screen. It is easy for us to ignore the seriousness of politics and to consider it as discontinuous with our own lives when we experience it mainly through a screen.

Postman was most worried about the political ramifications of treating everything as quick and uncomplicated entertainment. He thought the system of liberal democracy required citizens who were engaged and thoughtful, not citizens who turned everything into escapist entertainment. Many educated people around the world today are afraid that democracy is in a crisis. Do we in Canada still want freedom to influence our government's policies, do we think we still can, or have we decided it is hopeless and we just want to wallow in the entertainment possibilities of politics as delivered to us through the media? Certainly, the United States has increasingly seemed to find it difficult to make this distinction, and many recent leadership debates here in Canada haven't been any better, just less captivating as entertainment.

As discussed in the lesson on war, there is an assumption in the democratic model that the government will enact the will of the voters in its policies, including foreign policy. But a population that thinks of war on the one hand as an ever-present threat and on the other as a video game is unlikely to think about its government's military policies. The people who invented democracy as a system of government had started from the assumption that the common people can be trusted with the responsibility of democracy. They will see it is in their own interest to inform themselves and vote for what is best for themselves, their neighbours, the nation, and the rest of the world.

But this world of Donald Trump as President and America highly polarized upon Left vs Right and Democrat vs Republican has suggested to many people that if those things were ever the case, they may not be any more, especially since television became the model for representing reality in the media.

* Apparently, this well-known example is actually a bit of a myth, as it was based on somewhat flimsy data from one survey. In recommending caution, Marie Morelli added, however, that "The myth may have gained some currency from the reported reactions of the running mates. Both vice presidential candidates -- Henry Cabot Lodge for Nixon and Lyndon Baines Johnson for JFK -- thought their man had lost. Lodge watched on TV; Johnson listened on the radio." (Morelli 2016). Poorly substantiated or not, I think we can all easily see how it could have been true.