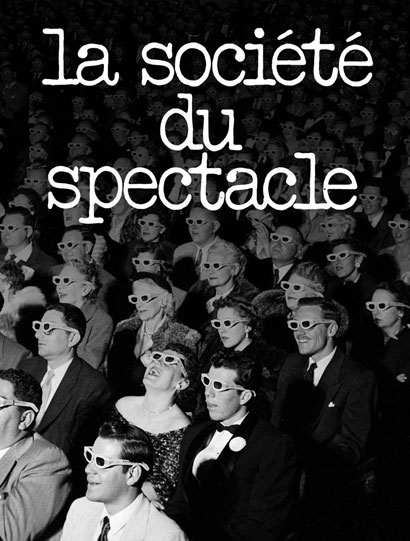

The society of the spectacle

At the same time Marshall McLuhan was telling us we were now "with it," a group of politicized artists and activists in France were suggesting that we were getting further and further away from it, meaning from real human life and reality, all the time.

Tomasz Fularksi, Pride 1

The Situationists, inspired by Marxist and post-Marxist critiques of Western culture, argued that industrialization and new broadcast media had perverted human relationships in an unhealthy and unnatural way. Previously our relations had been directly with each other and with nature, but we now related with other people through manufactured objects and images instead. For these critics, "All that once was directly lived has become mere representation" (Debord 1967). All human life is now mediated by products and unreal images. Products, consumer fetishes, brands, corporate and government propaganda, escapist fantasies, unrealistic "materialistic" ideals, partial images of reality created for the sake of entertainment or sensationalism - all of them manufactured for the rest of us by professionals working for companies who want to exploit us - had replaced real social life.

Guy Debord (the central Situationist) and his fellow activists believed that "everyday life"- life lived with other people doing meaningful practical tasks like making meals or working together - doing labour that was meaningful in itself, producing something of material worth (really material, not just symbolic), being creative rather than consuming other people's creations, was the natural and healthiest state for the human animal. They argued that with the industrialization of work and the invention of manufactured commodities, with the proliferation of endless images in mass media clogging any view of non-media reality, life had changed for the worse. The emerging culture of television, which encouraged people to forgo social relationships in order to sit at home on their couches and watch packaged human interaction as a "show," had brought about the emergence of a "Society of the Spectacle." We no longer engaged in life directly and participated in society out in the world: we sat back as spectators in our living rooms and consumed the "life" that was projected on our screens for us by the corporations that create our manufactured media.

Before the triumph of the Industrial Revolution, most human beings had experienced life directly and participated in it. When we were done working for the day, we ate dinner together, talked, played games together, made music for ourselves, went to church, worked in the garden, went for a walk, and so forth. We participated in culture and nature. In the 20th century, however, people living in the developed and wealthy parts of the world were able (and encouraged) to experience life in a passive and non-participatory way, through consuming film and broadcast media, television, advertising, brands, images. Instead of playing games ourselves in the open air, we sat and watched spectator sports on television. Instead of making music ourselves, we listened to music made by professionals on records or on the radio. Instead of doing a lot of things we would have done ourselves in the past, we sat back and watched a manufactured spectacle of "people" doing those things (or simulating doing things) on screens for our passive entertainment. We could feel that "life" was not something we were subject to ourselves, but something we were disconnected from, in control of (as long as we held the remote). The mass media was a crucial part of the consumer society. We were not just consuming products; we were consuming images of life, rather than fully living life ourselves.

The Situationists felt that the wealth of developed nations had led to a meaningless work life and alienated leisure time for the average human, filled with vicarious dreams of the "life" they saw on television and in ads. The Society of the Spectacle contributed to the emptiness of modern existence, because it made us passive, isolated and detached, inadequate-feeling, and driven to greater consumption and escapism, in hopes of somehow being "like the people on TV" rather than living our own lives realistically.

A more recent "far-Left" (by U.S. standards anyway) critic of consumer culture, Noam Chomsky, has talked eloquently of how he personally believes humans actually want to do things, not just be spectators, and how he believes an incredible amount of energy has to be expended by Hollywood, advertisers, and other manufacturers of mass culture to convince us that the world represented in the media is fascinating and important and that we will find happiness and success in consuming commodities and mainstream entertainment, living vicariously through consuming media.

I don't know whether I really believe that the working class people of Chomsky's youth read books and went to see Shakespeare plays, but I don't think he's just a nostalgic raver and romantic. I do believe that most people are happier and feel more alive when they are doing something, creating something, tinkering with an auto engine, say, fixing a broken table, or fixing dinner, than when they are watching other people do things as passive spectators.

Of course now we have the vicarious spectacle of watching people do crafts on TikTok, rather than doing them ourselves, dancing, playing with a pet. In a sense, with the Internet we have a much richer and more "real" vicarious spectacle to enjoy, from the comfort of our disengaged couchdoms. Does watching people make a meal or carve wood inspire us to do those things ourselves, or are we happy just to stand by and watch, consume without producing? Enjoy without participating. Partake, but only through voyeurism?

It's strange, if you think about it, that people can lie on the couch and get excitement through some kind of vicarious identification with onscreen lovers, adventurers, action figures. That vicarious identification is superbly satirized in the Simpsons "couch gag" sequence "LA-Z Rider" (a take off on the old tv series where a computerized car helped David Hasselhoff solve crimes (Knight Rider, 1982-1986)). Here, a motorized couch assists a fantasized version of Homer in experiencing a Miami Vice kind of exciting, sexy, fast-paced "life."

Amusing Ourselves to Death

Our addiction to the Spectacle can affect our behaviour as members of society in a negative way that I'll discuss further in the Democracy lesson. Many critics apart from Noam Chomsky have worried about the influence the mainstream media have on democratic citizens. They fear that overconsumption of these mostly showbiz "products" encourages people to become passive, dumber, less hopeful, more "materialistic" (consumerist), and more escapist, and that these are bad things in a democratic society. In the later lesson, I'll discuss more in-depth a few of the ideas put forward in Neil Postman's Amusing Ourselves to Death (1985, but still a relevant read today). Basically, Postman argued persuasively for the negative effects the broadcast media have on the depth of knowledge and understanding citizens have of their country, their world, and their governments, and just generally on their ability to tell reality from entertainment.

Postman pointed out how mass media culture (he was thinking mainly of TV) is mostly anti-intellectual and generally appeals to our emotions. Not just in sitcoms or crime dramas, but in news and more serious programming as well, the broadcast media tends to replace complex ideas and situations with simplified images. It tends to promote personalities rather than thought-out positions (think of Americans voting in former actor Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, or celebrity billionaire Donald Trump becoming president of the United States). Instead of arguments, this media tends to give you ads, "pitches." And it discourages active understanding and participation and encourages instead passive consumption and far-fetched fantasies. In short, it is escapist, simple-minded, unchallenging, and exploitative.

So it generally seems to me that what we were "with" in McLuhan's television era (the era I grew up in myself) was largely a manufactured media spectacle that takes our attention away from being fully alive ourselves. We are living through images of princesses getting married and three-pointers made from the comfort of our couches, rather than fully living our own lives in the world. Many of us have largely become spectators of life. And by "life," we actually mean the dead and repetitive media.