The division of labour

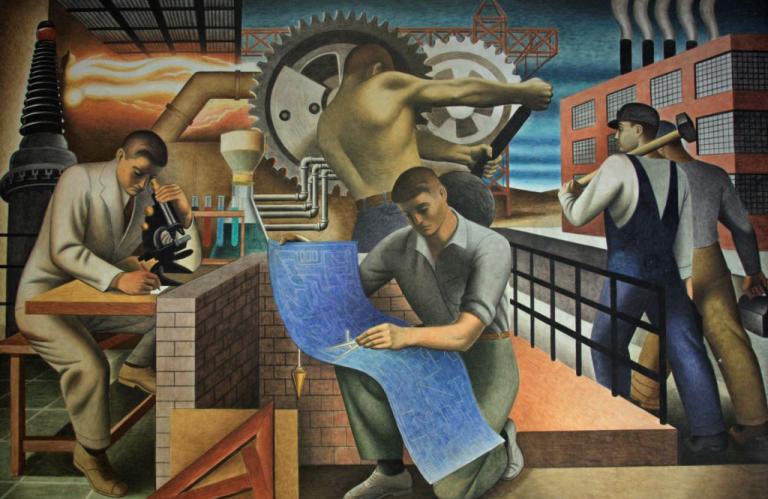

One of the things that led to the mechanization of human labour was the desire to replace skilled workers with less-skilled, and thus less expensive, labourers who could be responsible for a small repetitive task that didn't require much knowledge or understanding. This "componentization" of labour can be seen as part of the wish to replace humans entirely with machines. When there was part of a process that a machine couldn't do - or where a dedicated machine would actually be more costly than a person - it was expedient to replace that part with a human being. The task would typically be as repetitive as those which the machines were doing. The job would thus require little initiative, training, or education on the part of the component worker. The worker was encouraged to behave like a cog in a machine.

By the middle of the 1800s it had become clear to everyone that using human workers in this way had significant benefits from an economic point of view - and also serious costs from a human point of view. In his monumental critique of capitalism, Karl Marx drew particular attention to The Division of Labour as one of the chief evils of the modern world. The Division of Labour refers to the practice of dividing up the activity of producing or processing goods into small micro-jobs that can be handled by workers who do not need to understand the whole process, and may not even know anything about the whole picture or the final outcome of their small part in the system.

The paradigm of this type of labour would be a worker who stands at a position on an assembly line and whose job, for instance, is to operate a punch on an endless stream of metal parts moving past him. The worker doesn't even necessarily need to know whether the part is for a tv set, a surgical drill, or a nuclear warhead. His or her job is simply to punch the metal.

In the Middle Ages, if you wanted a table, you would go to a skilled craftsman. That person might well create the entire table for you on his own. It might take some time and the table would be a unique artifact. Even in larger ateliers where several craftsmen worked on the tables, all the workers knew and saw the full process of making the table; they might well know or have seen the person for whom they were making the table, and might eventually even see the look on the purchaser's face when he received the finished table. Their work had a certain amount of human meaning, in other words and they left the imprint of their own bodies and souls on the table thus created. There was a social and interpersonal dimension to it. The workers were not completely divorced from the beginning and end of the process of which they were a part. They understood the point of the work they were doing, and they were important to it.

With the division of labour all this changed. A worker might stand on the assembly line all day, attaching one leg to an endless line of uniform tabletops going by. There was much less reason for pride in one's work and less understanding of the full process: one was not fashioning a table but just attaching legs. One was not making tables, one was making a wage. No one person made the mass-produced table; no single worker created a complete table on their own.

Marx considered this a serious diminishment in the meaning and value of work. In his notes, he draws specific attention to the dehumanizing effect of this mechanization: "With the division of labour the worker is depressed spiritually and physically to the condition of a machine" (Marx 1844). Marx recogized that the average human being spends the majority of their waking life working. Consequently, in Marx's view, it was crucial that the work be meaningful to the worker and a healthy and organic social experience. Not that it be efficient or even lucrative, but that those precious hours of the worker's life would be spent doing something to which the worker was connected, for which they could feel some ownership and pride, and in which they had some say and were collaborating with others for the good of the collective.

If we look to our own day, the division of labour has, for the most part, only become more pronounced, and the alienation this causes more far-ranging. Think about a Chicken McNugget you might eat. Each part of the process is carried out by a different person or machine: the person who raises the chicken may not be the one who slaughters it; the person who takes the chicken to pieces and packages it is not the person who ships the package out or drives the truck that delivers it to the restaurant; the person who drops the processed chicken ball into the fryer and later retrieves it is not the person from whom you order the food - and none of these people is you, the person who actually eats it. This is the division of labour. And it allows you, the consumer, to ignore most of the chicken's story. It also allows everyone along the way to disconnect from any responsibility for the process they are taking part in.

In the "primitive" pre-industrial world most people raised their own chickens, slaughtered them themselves, dressed and prepared them. This was an organic process in which one was closely involved in all aspects of the chicken's life, death, preparation, and consumption. The work was meaningful, the chicken was meaningful, the whole thing was meaningful. We were connected to the chicken and its story. We knew what we were eating, what had gone into it, what it had cost. In the modern world all this has been vastly fragmented and no one is in touch with the whole chicken reality. The McNugget is meaningless. Arguably, this makes it a less meaningful meal.

As I'll come back to in the lesson on War, this disconnection and fragmentation of work may have dangerous implications for our humanity. The psychologist Stanley Milgram was famous for his electric shock experiments, in which ordinary people were convinced to deliver potentially lethal shocks to other ordinary people just in order to please the scientist in charge of the experiment. Milgram blamed the Nazi holocaust itself on the division of labour, the modern-day readiness to see workers as helpless parts of a machinelike chain, and of the workers themselves to consider themselves machine parts without responsibility for the consequences of the larger system of which they are only small components. We'll come back to Milgram and the division of labour in a couple of weeks.

Not only does the mechanization of work and the division of labour mean that most of us spend our days doing micro-tasks that are only a tiny part of a fully meaningful process, but it also means that none of us feels responsible for, or in many cases is even aware of, the full picture. It's a world of meaningless work and meaningless McNuggets. Disconnection from reality.

With the division of labour, as Stanley Milgram suggested, there is no clear accountability: who is responsible for the chicken's death? The person who raised it to be slaughtered? The person who actually kills it? The person who owns the company that sells chicken products? Or you - the person who pays to eat it? Our work activities become cogs in machines that are larger than the human scale on which people can actually live their lives, interact with each other, and take individual credit and responsibility, feel conscience. No one person can take credit for, and no one person can be held responsible for, most of the processes that happen in our modern world. Industrial mechanization has led to us acting in the world in ways that are too large for any one human being to understand or control. And has invited us to give over our personal and collective responsibility to an inhuman force: the system.

Some people feel that the effect this has had on our work lives has been devastating, though hardly anybody can remember or imagine now when things were different. The division of labour has made it possible for most of us to buy an affordable dining room table of uniform quality, and has put hundreds of other goods and luxuries at our disposal. The cost of mechanization has not been in buying power, not even necessarily in quality of goods (though that has sometimes been a cost). No: the cost has been in the meaningfulness of our work lives, and the sense of ownership and answerability we have for the work we do.

Most of us are both workers and "consumers," sometimes workers and sometimes consumers. Arguably, we gain as consumers but lose as workers in the modern world. It might be worth remembering that most of us spend more of our waking lives working than consuming...