Replacing people with machines

Machines have obvious advantages over human workers. They can work long hours without tiring; they don't need breaks; their work tends to be consistent and predictable; they do what you tell them to; they don't make mistakes, get sick, die, complain, go on strike, act out of malice – they don't have feelings. Do human workers have any advantages over machines? Purely from the point of view of efficiency one might be inclined to think not.

So as capitalism and industrial technology evolved and fed each other, it became increasingly attractive to those running manufacturing and other businesses to replace human workers with machines wherever possible. As they did, however, the very fabric of human existence was gradually torn apart. We went from a world where all of the goods in it were made or harvested by human hands, and held the traces of the human touch, to one where our goods often show no sign of human intervention. Work changed, and there was less chance for a human being to "put a piece of themselves" into the product of their labour. On the contrary, human beings were now encouraged to become less human at work, more like machines.

When we look at the human costs of the Industrial Revolution, the "fabric" of human life is indeed an operative metaphor. The earliest casualties of the Machine Age were those who worked in the textile industry – skilled weavers above all. You may have heard people who don't like new technology – someone who refuses to get a smartphone, for instance – referred to as Luddites. Let me fill you in on Ned Ludd and the Luddites, who always sound to me like they would have made a hell of a punk band.

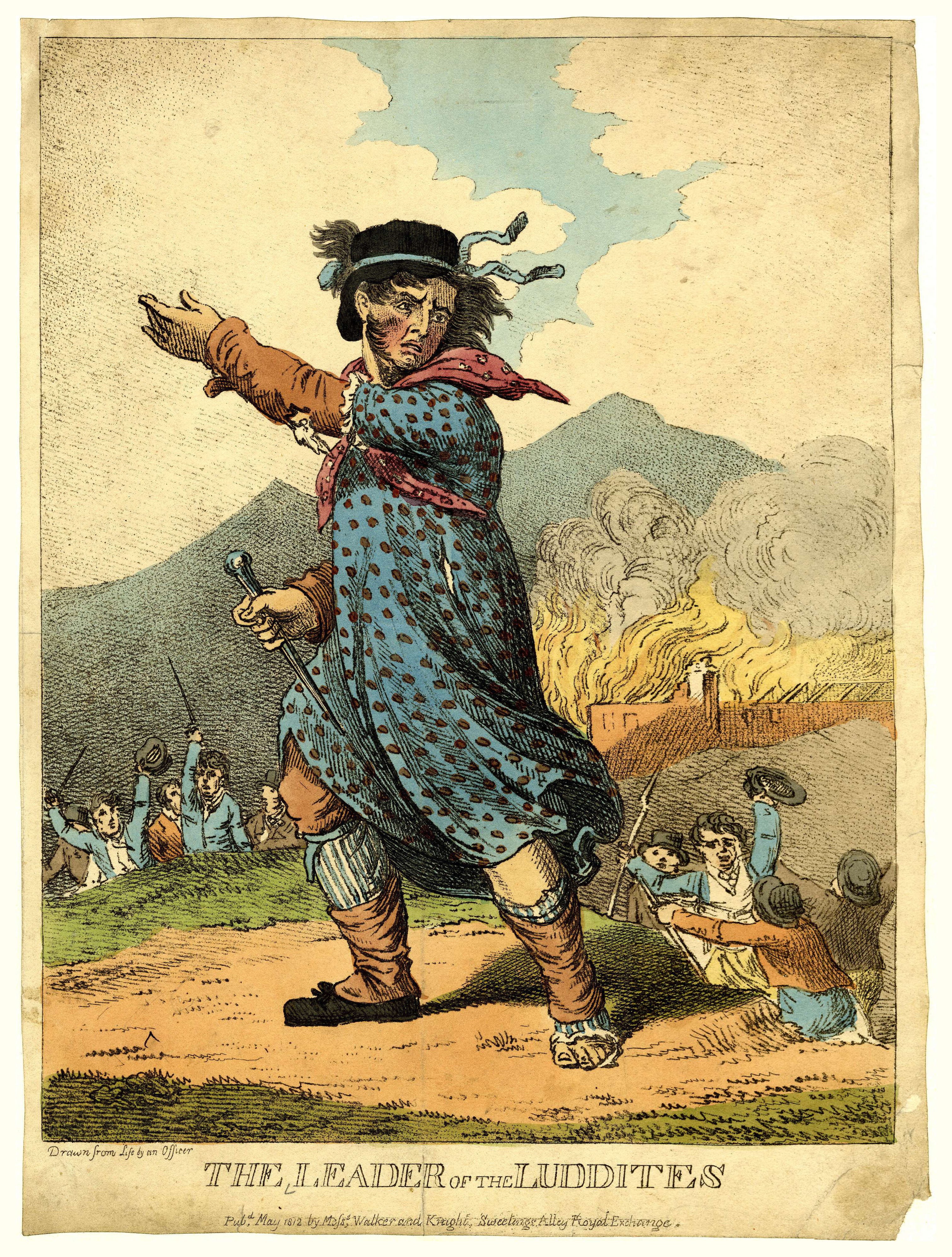

The original Luddites were activists who took a stand against the automation of the weaving industry by lashing out with violent acts of resistance. We're talking England in the early 1800s here.

The Luddites named themselves after a possibly mythical individual, Ned Ludd, a young man who supposedly destroyed two knitting machines "in a fit of passion" in 1779. Ludd's story is obscure and was only reported much later, so it may be at least partly fictional, but the character became a folk hero - something like Robin Hood - and was used as a rallying symbol by the later textile workers who sometimes referred to him as "General Ludd" or "King Ludd."

Between 1811 and 1817 Luddites smashed textile machines, organized other forms of sabotage and rebellion, and protested publicly against the mechanization of their trade, a change that allowed them to be replaced by machines and low-cost, unskilled labourers. At times the protesters met secretly; others faced off in the open against the forces of the British army, protecting the interests of the factory owners.

A stocking frame, the machine supposedly attacked by Ned Ludd, and one of the main targets of the Luddites.

The Luddite uprising was a fierce challenge to the forces of progress. Although the Luddites had their defenders in parliament, including the poet Lord Byron, the violent and destructive activism of the movement led the government to call out the army and to make machine-wrecking a crime punishable by death! The machine is thus recognized here as worth as much or more than a human life.

The movement was eventually repressed or died out, and of course progress marched forth creating more and better machines to do the work that human beings had traditionally done.

The Luddite insurrections were a famous episode in what was really a much larger reaction on the part of working class people who were left unemployed or whose skills became obsolete because of mechanization. The machines were a target for the frustration of those whom they had put out of work. A similar kind of violence broke out later, in the agricultural sphere, during the Swing Riots of the 1830s, when protesters destroyed threshing machines, set fire to granaries, and so forth. The people did not easily give over their work to the machines.