Life on the clock

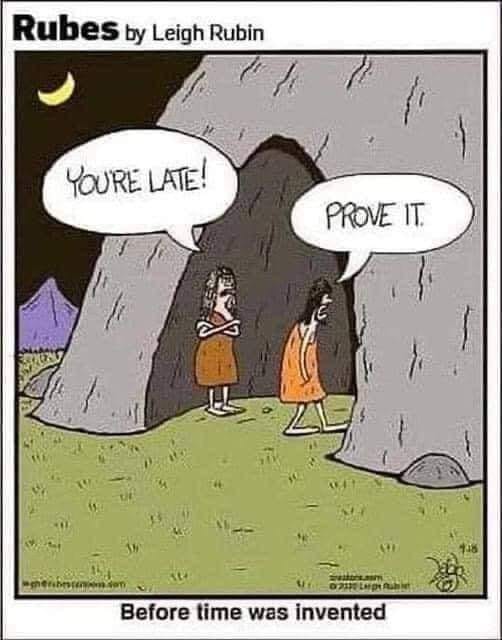

How did human life change with the invention of the mechanical clock? The positive benefits once the clock and watch became common might include such things as precise scientific measurements of duration, speed, and so forth. Also, people could now be on time for appointments (or late). Time-limits could be imposed accurately. People could be paid by the hour, and the workday could have a beginning and end unrelated to the tasks at hand or natural daylight.

Here already in these benefits we may also sense a hint of the reservations about mechanical time that some of its theorists have. Is life actually better with mechanical time? Fuller? Richer? Happier? Heathier? More organic? More meaningful? More real? In what ways is it better, and in what ways is it actually perhaps worse for the average person?

A general assumption in the history of science is that every innovation has not just the good effects for which it was intended but also many unintended consequences, some of which are ultimately negative. What are the intended and unintended consequences of the mechanical clock?

The clock's critics, like the anarchist George Woodcock quoted earlier, point out that with mechanical time human beings are torn out of the fluid, real, organic time that passes in nature and stuck into a man-made mechanical system of mathematical abstractions - hours, minutes, and seconds – that have no basis in nature and no natural meaning. We become alienated from the environment, and increasingly enslaved to a human construct that can be measured, monitored, and monetized, but has no relation to the workings of our physical bodies and souls.

Now the movement of the clock sets the tempo of men's lives - they become the servant of the concept of time which they themselves have made, and are held in fear, like Frankenstein by his own monster. In a sane and free society such an arbitrary domination of man's functions by either clock or machine would obviously be out of the question. The domination of man by the creation of man is even more ridiculous than the domination of man by man. Mechanical time would be relegated to its true function of a means of reference and co-ordination, and men would return again to a balanced view of life no longer dominated by the worship of the clock. Complete liberty implies freedom from the tyranny of abstractions as well as from the rule of men. (Woodcock 1944)

Clocks are frequently a symbol of murderous control in the arts, and we all sense, I think, the perversity of the human animal shackled to the machine of time. In the film David and Lisa (1962), based on a real-life story, the patient David has a dream in which he controls a scythe-like minute hand on a giant clock with his psychiatrist's head marking the approaching hour.

Humans shaped the tool of the clock, and now we have been shaped (and perhaps misshaped, warped, distorted) by it. This dislike for the "mechanization of humankind" may sound quaintly old-fashioned and naive to some of you, but it would be foolish to ignore the essential truth in these admittedly anti-progress criticisms: the mechanical clock took something away from humans and imposed something new on them that they didn't necessarily want or enjoy. The benefits of this technology are myriad, but there were real costs as well. And some would argue that these costs were actually part of a radical and profound change in human existence from which we have not yet recovered. The disconnection from nature, and our own natures.

This class is about how technological innovations change how we are human. For the better, and perhaps at times for the worse.